Scientists on a research expedition onboard Schmidt Ocean Institute’s R/V Falkor (too) reportedly located Chile’s deepest and most northern cold seeps. At 2836 meters deep, the seeps provide chemical energy for deep-sea animals living without sunlight, offering potential insights into the conditions that led to the development of life on Earth.

The search for the seeps took over 12 hours, as scientists examined an area with geologic features that led them to suspect there might be seeps. Their investigation relied on seafloor mapping data and data interpretation from local and international experts. Shallower cold seeps, like methane seeps, are usually located by finding bubbles coming from the ocean floor in SONAR data; the soundwaves sent to the seafloor that are used for mapping it. The bubbles are not always visible for deeper seeps, making locating them more challenging.

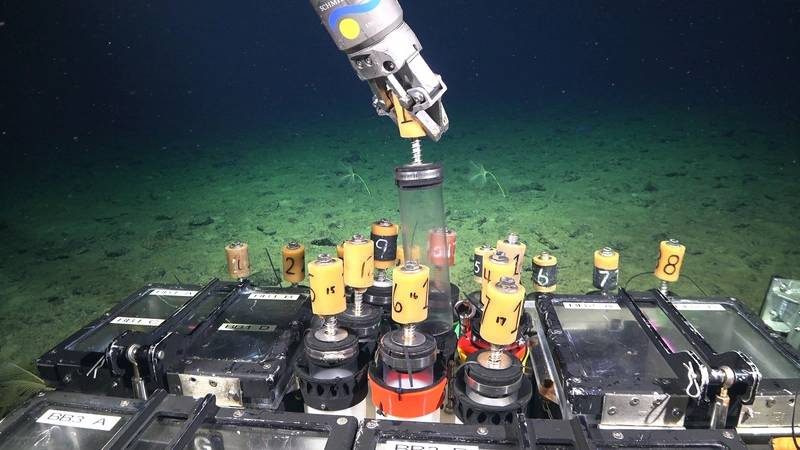

The expedition’s Co-Chief Scientist, Dr. Lauren Seyler of Stockton University, New Jersey, USA, led the seep-finding endeavor. The effort was a collaboration between Seyler and Drs. Antonio Molina and Oscar Ercilla of Centro de Astrobiología (CAB, CSIC-INTA) in Madrid, Spain, Science Coordinator Jessica Eberle, and the R/V Falkor (too)’s marine technicians, with additional support from Dr. Andrew Palmer of Florida Tech, Melbourne, Florida

Visual evidence strongly suggests that the seeps found by the team are methane seeps. These seeps are chemosynthetic ecosystems where naturally occurring methane bubbles up from fissures in the seafloor. They are formed along subduction zones, ocean areas where two tectonic plates collide and one is pressed under the other. Methane on the seafloor provides energy for bacteria, a food source for animals like clams, squat lobsters, and tube worms. The seeps located during the expedition are in the Atacama Trench, an 8000-meter-deep formation that runs the length of Peru and Chile. Astrobiologists are especially interested in studying seeps because they give insight into how life developed on Earth and how those survival strategies and chemical conditions might sustain life on other planets.

“The microbes that live on these seeps have amazing strategies for producing food without sunlight,” said Dr. Seyler. “Here on Earth, life in the dark is alien in its own right and provides critical information for understanding how organisms persist under the most extreme conditions. We are still trying to figure out how life started on Earth, and environments that provide chemical energy for life, like this one, might offer clues about the spark that ignited all the biodiversity on our beautiful planet.”

A gossamer worm (a type of Tomopteris Polychaete) documented in the water column during Dive 682, as the expedition explored a ridge area near continental slope of Chile, searching for seeps and associated communities.

Credit: ROV SuBastian / Schmidt Ocean Institute

The seeps were found off the northern coast of Chile near the Atacama Desert, Earth’s oldest desert. The Atacama has barely changed location for the past 150 million years. Researchers like the expedition’s Chief Scientist, Dr. Armando Azua-Bustos of Centro de Astrobiología (CAB, CSIC-INTA), have found interesting microbes in the desert from ancient lineages that give insight into the evolution of life on our planet. Searching for the methane seeps was part of a wider expedition goal of determining if the deep ocean adjacent to the desert also contains ancient microorganisms, as suggested by Azua-Bustos and his collaborators’ research on land.

“The Atacama Desert is a well-known Mars analog model here on Earth. It contains precious insights for how life, if it ever arose on Mars, might be able to adapt to an increasingly drying plane,” said Dr. Azua-Bustos, “We hope the information we gathered from the Atacama trench, with help from the Schmidt Ocean Institute, will aid us in searching for biosignatures should we eventually study the oceans of Enceladus and Europa on Saturn and Jupiter, water worlds that may potentially support life.”

The science team, including Dr. Guillermo Guzmán, Dr. Nikolaos Schizas, and Professor Alexis Gacitúa, also collected more than 70 specimens, with many species suspected to be new to science. Pending further research, the suspected new species found between 3000 and 4500 meters’ depth include marine snails and amphipods. Other specimens include brachiopods, leptochitons, and crinoids, which are hypothesized to be close descendants of fossils found in the Atacama Desert. The animal samples will be kept at the Universidad Arturo Prat Museo del Mar in Iquique and the National History Museum in Santiago, Chile, following identification and characterization.

“Finding such cold-water seeps using nothing but mapping data is wonderful,” said Dr. Jyotika Virmani, Executive Director of the Schmidt Ocean Institute, “There was a chance that the science team would not locate these amazing deep-water, chemosynthetic environments. With further analysis, bacteria from these seeps may provide new insights into how life persists in the darkness, offering scientists guidance on how and where to search for microbial life elsewhere in our solar system.”

Isabel Herreros (Scientist, Centro de Astrobiología, CSIC-INTA) and the team work in the Dirty Wet Lab on Research Vessel Falkor (too) as SuBastian nears the surface.

Isabel Herreros (Scientist, Centro de Astrobiología, CSIC-INTA) and the team work in the Dirty Wet Lab on Research Vessel Falkor (too) as SuBastian nears the surface.

Credit: Alex Ingle / Schmidt Ocean Institute