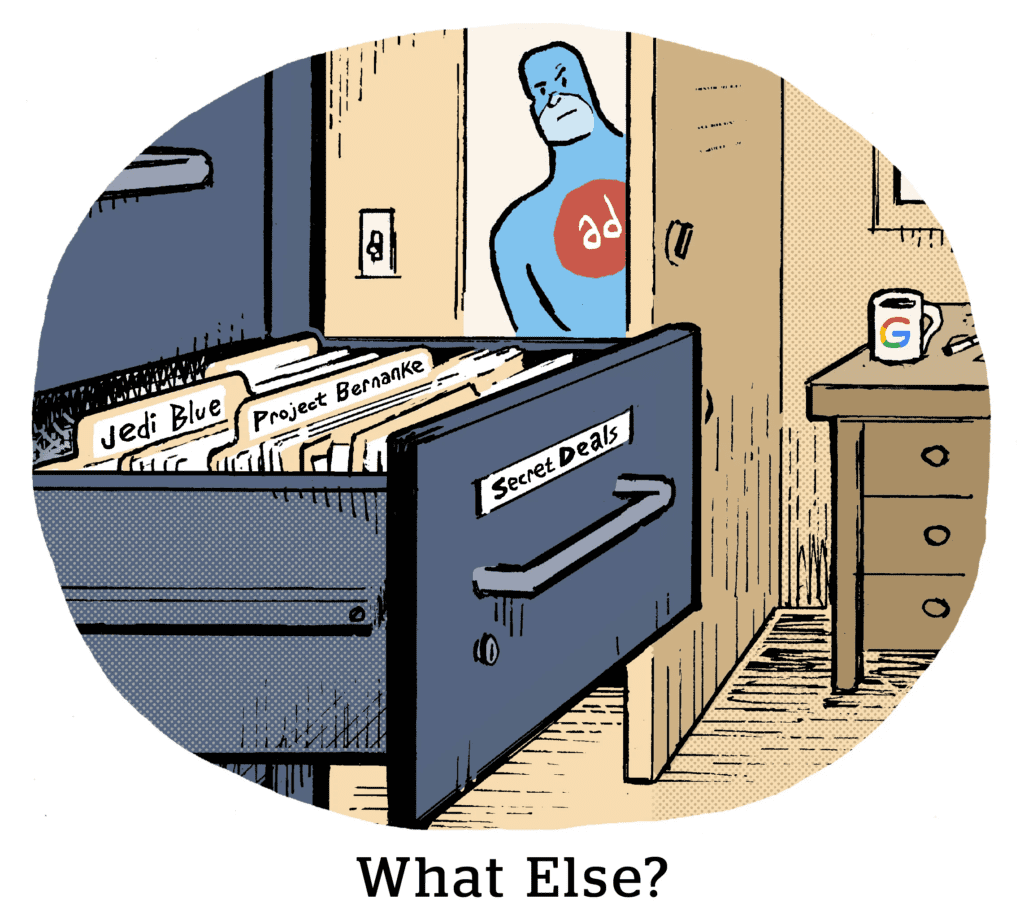

What do Hercule Poirot, Ben Bernanke, Star Wars and C.S. Lewis have in common?

If you’re an ad tech nerd, you’ll know the answer immediately.

They all served as inspiration for the code names associated with different internal Google projects that came to light as part of the DOJ’s ad-tech-focused antitrust lawsuit against Google.

The disclosure of these initiatives generated much discussion over the past couple of years, but it’s unlikely we’ll see the government get into the weeds on them during the trial itself, which is set to begin on Monday morning in a Virginia federal court.

You can take off your tinfoil hat now

The details of each initiative are highly technical and not strictly necessary for the Department of Justice to make its case.

If, for example, the DOJ can prove Google maintained a monopoly in the ad server market and used its ad server (formerly DFP) to advantage other parts of its ad tech stack, including AdX, that could be enough.

But whether they’re cited during the trial, revelations about Google’s internal projects – especially those related to Google’s header bidding countermeasures – were deeply validating to publishers and third-party ad tech platforms.

Guess it’s not paranoia if they’re really out to get you?

As one ad tech executive close to the trial told AdExchanger on background, learning more about Project Poirot and Project Bernanke was like discovering “all that stuff we hear about late at night at the bar was really real.”

Project Cheat Sheet

And now the trial is really starting.

But first, let’s take a brief stroll down Codename Memory Lane. Here’s a recap of all the Google projects highlighted in the DOJ’s complaint – and a few you may not be familiar with that were cited in related court filings.

Jedi

To say that Google wasn’t a fan of header bidding is an understatement.

In an effort to counter it and maintain control while seemingly throwing exchanges a bone, Google devised Jedi, its internal codename for exchange bidding (which later became open bidding).

Through Jedi, Google would allow rival exchanges to compete with its platform in real time, but with certain limitations. For example, Google continued to operate a second-price auction and still had last look.

It’s worth noting that the DOJ’s complaint doesn’t reference Jedi Blue – at least not by that name. Jedi Blue was the cooperation agreement whereby Google would charge Facebook lower fees and give Facebook advantages in header bidding auctions, such as speed and information, in exchange for Facebook supporting Google’s open bidding product.

But Jedi Blue does make an appearance in the complaint under another name – “Network Bidding Agreement” – which means the details could come up at trial.

(Although a federal judge in New York ruled in 2022 that the agreement between Google and Facebook was not unlawful and dismissed that aspect of a separate Texas-led ad tech-focused antitrust case against Google, it’s since become fair game again after Congress passed a law that allows state attorneys general to keep antitrust cases within the jurisdiction they were filed in. Discovery was reopened in the Texas case and that trial is slated for 2025.)

Project Bernanke

According to the DOJ, Google launched Project Bernanke in 2013 as “a secret scheme to manipulate the bids” that Google Ads submitted into its ad exchange, AdX, “in order to win more competitive transactions and solidify AdX’s dominance in the industry.”

The DOJ alleged that this allowed Google to “suppress competition by preventing rival ad exchanges from achieving the transaction volume and scale necessary to compete.”

Although Project Bernanke features prominently in the DOJ’s 2023 suit, details about it were first revealed in 2021 when an unredacted version of the Texas-led lawsuit against Google was mistakenly shared with The Wall Street Journal.

Project Bernanke was named after Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, because it resembled “quantitative easing on the ad exchange.” Hardy har.

Global Bernanke

Project Global Bernanke, implemented in 2014, tweaked the way Google calculated its margin in Google Ads by applying different take rates to different publishers. The take rate was allegedly higher for publishers that were unlikely to switch to a rival ad server.

For example, Google could use its position on both the buy side and the sell side to charge advertisers based on the highest bid, pay publishers on a low bid and use the difference to increase the bid price to win subsequent auctions in favor of more “important publishers.”

Starting in 2014, the DOJ says Google recalibrated Project Bernanke to decrease bids from Google Ads on AdX for publishers that allowed rival exchanges to buy inventory before AdX.

Through Project Bell, as it was called, Google would reduce bids without telling the advertiser by roughly 20%, and it allegedly told publishers that using “first-call” technology, aka header-bidding technology, would cause their yield to drop by 20% to 30%.

According to the DOJ, this “both insulated Google’s ad exchange from this new form of competition and preserved preferential access for buyers on Google’s ad exchange, including Google Ads.”

Project Bell was named after Alexander Graham Bell, who made the first call. (h/t to Digital Content Next CEO Jason Kint for unearthing a 2014 email exchange between Google employees noodling on a name)

Project Poirot

By 2016, Google moved on to Project Poirot, an effort, as the DOJ put it, to blunt header bidding by “drying out” the competition.

This involved shifting transactions toward AdX and away from ad exchanges that were using header bidding.

Google changed the settings within DV360 to opt advertisers into Project Poirot by default – only 1% opted out – and then lowered the bids from DV360 to rival exchanges by 10% to 40% and eventually by as much as 90%, putting AdX in a position to win those bids.

Project Poirot was named after Agatha Christie’s iconic and extremely clever Belgian detective character, perhaps because Google employed a rather clever tactic to detect exchanges engaging in header bidding. If an exchange no longer used a second-price auction, that was a pretty good sign that they were using header bidding.

Project Narnia

When Google acquired DoubleClick, there were privacy policies in place prohibiting Google from combining its user data from Search, Gmail, YouTube and other properties with data gathered from non-Google sites.

Project Narnia, in 2016, involved Google changing that policy so all user data could be combined into a single ID. The DOJ argues that this “proved invaluable to Google’s efforts to build and maintain its monopoly across the ad tech industry.”

Who knows why it was called Project Narnia, considering Narnia is an allegory for Christianity. Would love to hear your theories.

Project Alchemist

This one doesn’t appear in the DOJ’s complaint, but does get briefly referenced in other court filings, including an expert report for the plaintiff by Robin S. Lee, a professor of economics at Harvard University.

In a footnote about Projects Bernanke and Bell, Professor Lee mentions that, in September 2019, Google Ads updated the Bernanke algorithms to be compatible with a unified first-price auction but without changing Google’s take rate.

The new algorithm was referred to internally as “Alchemist” … maybe because it was margin magic?

And now the lawyers get their turn

And now the lawyers get their turn

The ad product folks aren’t the only ones who get their own codenamed projects at Google.

There are mentions of multiple other projects in a few court documents, primarily related to Google’s efforts to analyze the global regulatory landscape and come up with solutions.

There’s not much information on these so-called “Remedy Projects,” which is how Google’s lawyers referred to them within a motion they filed to keep related documents under privilege.

But, all the same, it’s interesting to see where Google’s focus has been.

Project Sunday and Project Monday

These were analyses of potential changes that could be made to Google’s ad tech business in light of global regulatory investigations.

Project Stonehenge and Project SingleClick

These two also appear to have been about analyzing possible remedies in response to regulatory interest in Google around the world.

Project Stonehenge specifically was an assessment of the implications of ongoing antitrust inquiries.

According to a redacted December 2021 deposition of an unnamed Google employee, people on the Google Ad Manager team were in charge of Project Stonehenge. It ended in June 2020.

Project 1Door

This was a proposal to streamline the three “buying doors” for Ad Manager and AdMob, presumably DV360, authorized buyers and the Google Display Network. Hence, one door.

It also involved an assessment of implications and options in response to potential regulatory inquiries.

Project Banksy

You may be sensing a theme: Project Banksy also refers to an analysis that was conducted of potential remedies in response to antitrust regulatory investigations.

Project Quantize

A request within Google for legal advice regarding compliance with privacy and competition laws.

Project Garamond

Very few details on this one. It has something to do with a news content licensing program.

Project Metta

Finally, Project Metta (not to be confused with Meta or Mehta!) is Google’s initiative to understand and ensure compliance with the Digital Markets Act in Europe, which is legislation to regulate the behavior of large digital platforms. The DMA was passed in 2022 and is now in effect.

Metta is also Google’s response to ongoing antitrust regulatory investigations in Europe, Australia and the UK.

And that’s it. We’re done. No more projects … that we know of?

Update 9/6/24 at 2:52 p.m. ET: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said that Jedi Blue was completely off the table.