By Nick Edser, Business reporter, BBC News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPay is rising at its slowest rate in almost two years as the job market continues to cool.

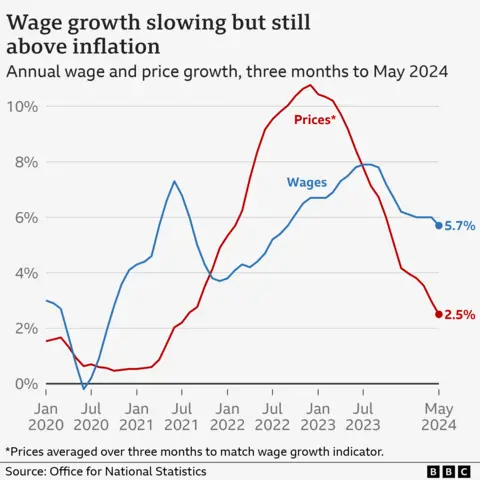

Wages grew at an annual pace of 5.7% in the three months to May, but they are still outpacing rising prices.

The number of job vacancies has fallen while the unemployment rate remained at 4.4% in the three months to May, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said.

Economists are debating whether the numbers will encourage the Bank of England to cut interest rates next month, with the decision expected to be very close.

Liz McKeown, ONS director of economic statistics, said that pay growth, “while remaining relatively strong, is showing signs of slowing again”.

“However, with inflation falling, in real terms it is at its highest rate in over two and a half years.”

After taking the impact of inflation into account, wages were up by 3.2%.

The speed of pay growth is one of the things the Bank of England will consider at its next meeting on 1 August when deciding what to do about interest rates.

The Bank tends to raise interest rates – or keep them high – when it believes inflation or wages are rising too quickly, hoping that pricier debt will slow down price and pay increases.

If wages are growing strongly, this can push up costs for firms, which they may seek to offset by increasing prices to consumers.

Inflation data released on Wednesday showed it was unchanged at 2% – in line with the Bank’s target, giving some confidence that rates could be cut.

However, price rises in the services sector, which covers business such as restaurants and hairdressers, remained strong.

Ashely Webb, UK economist at Capital Economics said that, while the slowdown in pay growth was “encouraging”, he doubted it would be enough to offset concerns about persistent inflation in services.

“We now expect the Bank to cut interest rates from 5.25% to 5.00% in September instead of August,” he said.

Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK, said the “modest” slowdown in pay growth “offers some good news for those looking for a rate cut in August”.

“But with annual pay growth excluding bonuses at 5.7%, the Bank of England may be unwilling to risk an August cut in rates before the labour market has cooled sufficiently,” she added.

Pay growth in the private sector slowed to 5.6% from 5.9% in the previous three months, the ONS said, while it stayed unchanged at 6.4% in the public sector.

Earnings grew fastest in the finance and business services sector, up 6.7%, while the construction sector saw the smallest rise, with an increase of 3.0%.

Ms McKeown said: “We continue to see overall some signs of a cooling in the labour market, with the growth in the number of employees on the payroll weakening over the medium term and unemployment gradually increasing.”

Between April and June this year, the number of job vacancies fell by 30,000 on the quarter to 889,000, led by the retail and hospitality sectors.

The number of vacancies has now been falling for two years, but still remains higher than pre-coronavirus pandemic levels.

The rate of people considered “economically inactive” – defined as those aged between 16 to 64 years old not in work or looking for a job – edged lower to 22.1% in the March to May period, the ONS said.

It means about 9.4 million people are classed as “inactive”, with the figure about 800,000 higher than before the coronavirus pandemic.

Concerns have been raised over worker shortages affecting the UK economy.

Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall said the new government had been given “a truly dire inheritance”.

“Spiralling economic inactivity, rising unemployment and the UK standing alone as the only G7 country where the employment rate is still not back to pre-pandemic levels.”

One of the problems the Bank of England and others have had in using the jobs data recently is questions over the reliability of the figures.

The Labour Force Survey conducted by the ONS, which produces the data, has had a smaller number of respondents over the past year than normal.

The ONS has been developing a new version of the survey, but it said on Thursday this was still being worked on and it would report back on progress early next year.