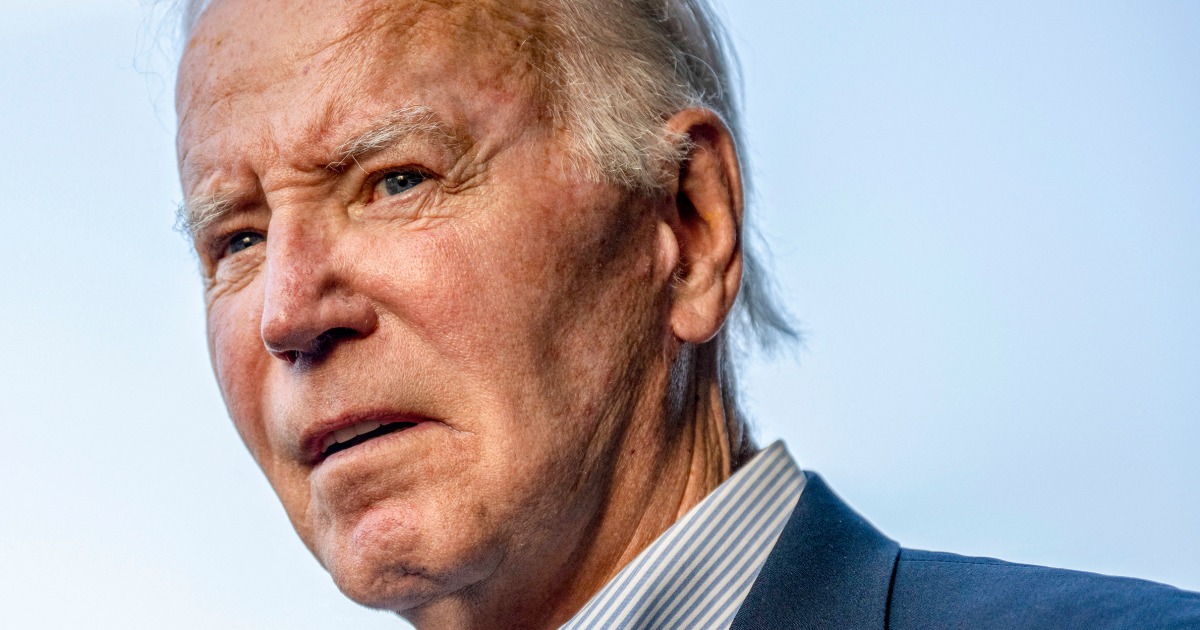

President Joe Biden is launching a new phase of his presidency this week.

Liberated from the constraints of a re-election campaign, he’s in the beginning stage of a strategy that will take him to places at home and abroad over the next five months that he most likely would have ignored as a candidate, not with the goal of keeping the White House, but of keeping his legacy and some of his most significant accomplishments secure.

On Thursday, Biden travels to a small town in a county in southwest Wisconsin that had voted reliably Democratic for two decades until Donald Trump carried it twice. Biden will make more trips like these, to Republican-leaning areas — and even eventually red states — to make the case that his agenda has also benefited those who voted against him, according to multiple Biden advisers.

Aides are also reallocating time Biden had reserved for domestic politics to focus instead on foreign policy, with plans for an international farewell tour of sorts that could include a long-promised trip to Africa in October.

“The schedule will be robust and he plans to leave it all on the field,” White House communications director Ben LaBolt said.

Biden enters the twilight of his presidency with little recent precedent to guide him. Re-elected presidents begin their second terms knowing they have years to begin shaping their legacies. Recent one-term presidents, on the other hand, were fighting until their final weeks to hold onto the office.

Yet, one senior Biden adviser noted that the president has been mindful of the weight of history since the moment he first entered the Oval Office, weeks after the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol and amid public health and economic crises.

“It’s been ever present, because the stakes have been so high,” the adviser said.

Still, the president’s aides said a new approach was required after Biden made the consequential decision in late July to end his bid for a second term and endorse Vice President Kamala Harris to replace him on the Democratic ticket. One of the first directives Biden gave after bowing out was to his chief of staff, Jeff Zients, saying he wanted his final months in the Oval Office to be as consequential as any similar period in his term so far.

In general terms, that meant implementing the pillars of his legislative record — infrastructure investments, boosting manufacturing, climate change initiatives and expanded veterans care — while looking at where the president can lay the groundwork for unrealized or even new policy ideas that would give a potential Harris administration a running start.

Zients then set about working with other top advisers to put a specific action plan in place, the early contours of which were presented to Biden when he began a two-week, bicoastal vacation following his farewell speech at the Democratic National Convention on Aug. 19, Biden aides said.

Advisers said it focuses on four goals: finding new ways to increase investment in U.S. infrastructure; reducing costs for Americans; safeguarding freedoms the president believes are under siege; and strengthening U.S. alliances to confront global challenges.

Each goal aims to burnish Biden’s legacy, but the president’s aides said they also will help make a case against Trump that they hope will help Harris’ campaign.

“Good governance is a way to show contrast,” one official said.

Biden’s team is regularly in touch with the Harris campaign operation — one, advisers note, they largely built — to ensure the president’s actions are helpful, Biden aides said. The goal, they said, is for Biden to act “surgically” and to campaign where it is “strategically impactful” for him to go, as one of them put it.

The plan is for Biden to focus on constituencies where he has had appeal, such as senior voters and blue-collar communities, aides said.

The Biden official also argued that the president’s record continues to be popular among Democrats. “It’s not like 2008,” the official noted, when then-President George W. Bush was poised to leave office with approval ratings as low as the 20% range and an economy in free fall.

Much of Biden’s domestic travel will be under the guise of official administration business, such as stops he plans Thursday and Friday in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Biden also is expected to travel extensively overseas, including in October after the annual gathering of world leaders in New York for the United Nations General Assembly, according to two senior administration officials and two former senior U.S. officials familiar with the plans.

The possible countries he could visit in October, as the presidential campaign is at a fever pitch, include Germany, as well as at least one stop in sub-Saharan Africa, the officials said.

None of the ideas under discussion have been finalized on the president’s schedule, one of the senior administration officials said, adding: “The team is pulling together options.”

Biden does plan to travel to Brazil for the Group of 20 summit and to Peru for a gathering of Asia-Pacific leaders, officials said. He is looking to hold high-profile meetings with key world leaders, including at the U.N. General Assembly later this month and a potential meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in November on the sidelines of the G20, the officials said.

Since dropping out of the 2024 race, Biden has had a lot more time to devote to foreign policy matters than his senior aides had planned for when they thought he would be campaigning nonstop for re-election, the officials said.

“His foreign policy agenda is very full” in these final months, according to White House National Security Council spokesman Sean Savett.

Now, Biden can chat longer on the phone with world leaders, extending calls that previously would have been curtailed with a more jam-packed schedule. In recent conversations, the president has mentioned to his counterparts that he looks forward to seeing them again before leaving office and has even joked about how much more free time he has on his hands, a Biden aide said.

While Biden’s goals for his final months in office are set, specific plans beyond September remain subject to change, aides said, noting the presidency naturally comes with unseen events.

His role in the campaign won’t be as robust as then-President Barack Obama’s was eight years ago for then-Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, which included regular campaign events in battleground states including a large, closing joint rally in Philadelphia.

But Biden aides pointed to the president’s event Monday in Pittsburgh as indicative of what they believe he can do for Harris, starting with vouching for her character and commitment to supporting the kind of working- and middle-class voters he has long considered his political base.

“We can help strengthen the argument, fortify the argument for her in the way that we did as vice president to President Obama, and the same way Vice President Harris helped us to win in 2020,” the senior Biden adviser said.

On Tuesday at a White House event, Biden said he would in the weeks ahead “talk with Americans all across the country about the progress we’re seeing in their communities.” He also indicated he wants to make the most of his final months there.

“I’m not going to be in the White House much longer, but you got to come and see me,” Biden told the four local officials who participated virtually in Tuesday’s event.