Getty Images

Critics of spyware and exploit sellers have long warned that the advanced hacking sold by commercial surveillance vendors (CSVs) represents a worldwide danger because they inevitably find their way into the hands of malicious parties, even when the CSVs promise they will be used only to target known criminals. On Thursday, Google analysts presented evidence bolstering the critique after finding that spies working on behalf of the Kremlin used exploits that are “identical or strikingly similar” to those sold by spyware makers Intellexa and NSO Group.

The hacking outfit, tracked under names including APT29, Cozy Bear, and Midnight Blizzard, is widely assessed to work on behalf of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service, or the SVR. Researchers with Google’s Threat Analysis Group, which tracks nation-state hacking, said Thursday that they observed APT29 using exploits identical or closely identical to those first used by commercial exploit sellers NSO Group of Israel and Intellexa of Ireland. In both cases, the Commercial Surveillance Vendors’ exploits were first used as zero-days, meaning when the vulnerabilities weren’t publicly known and no patch was available.

Identical or strikingly similar

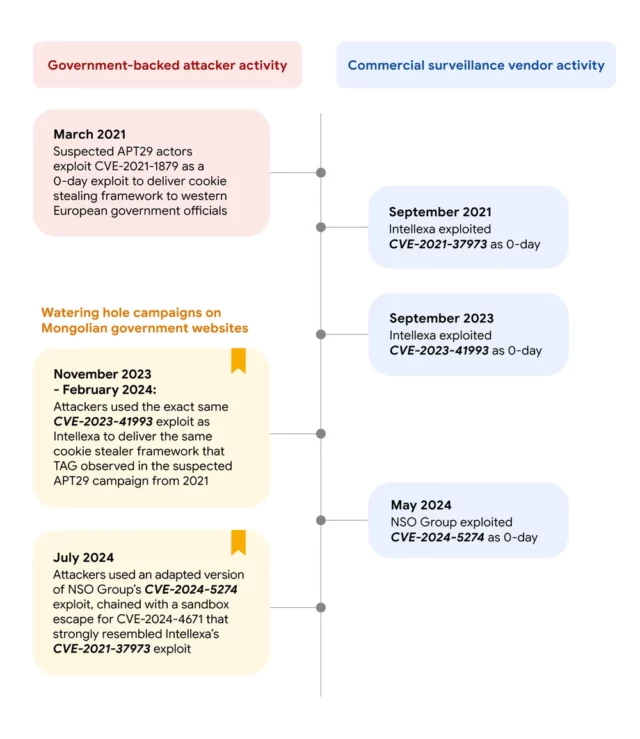

Once patches became available for the vulnerabilities, TAG said, APT29 used the exploits in watering hole attacks, which infect targets by surreptitiously planting exploits on sites they’re known to frequent. TAG said APT29 used the exploits as n-days, which target vulnerabilities that have recently been fixed but not yet widely installed by users.

“In each iteration of the watering hole campaigns, the attackers used exploits that were identical or strikingly similar to exploits from CSVs, Intellexa, and NSO Group,” TAG’s Clement Lecigne wrote. “We do not know how the attackers acquired these exploits. What is clear is that APT actors are using n-day exploits that were originally used as 0-days by CSVs.”

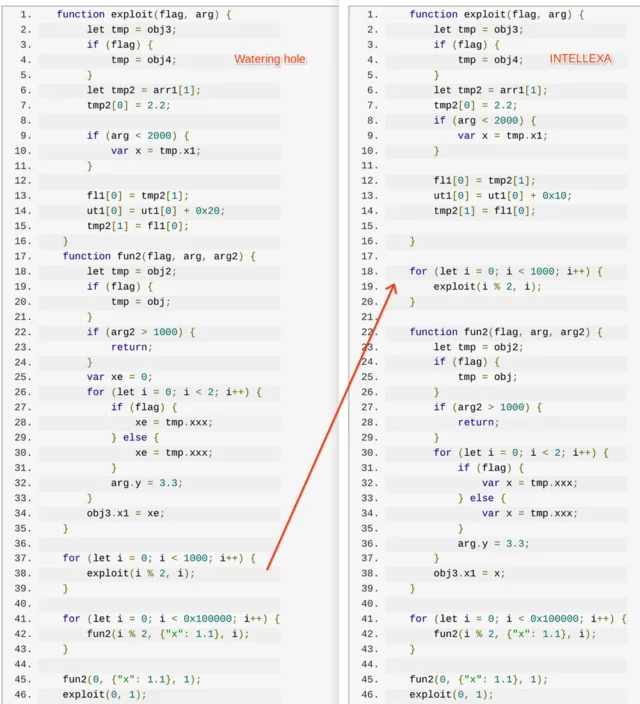

In one case, Lecigne said, TAG observed APT29 compromising the Mongolian government sites mfa.gov[.]mn and cabinet.gov[.]mn and planting a link that loaded code exploiting CVE-2023-41993, a critical flaw in the WebKit browser engine. The Russian operatives used the vulnerability, loaded onto the sites in November, to steal browser cookies for accessing online accounts of targets they hoped to compromise. The Google analyst said that the APT29 exploit “used the exact same trigger” as an exploit Intellexa used in September 2023, before CVE-2023-41993 had been fixed.

Lecigne provided the following image showing a side-by-side comparison of the code used in each attack.

Google TAG

APT29 used the same exploit again in February of this year in a watering hole attack on the Mongolian government website mga.gov[.]mn.

In July 2024, APT29 planted a new cookie-stealing attack on mga.gov[.]me. It exploited CVE-2024-5274 and CVE-2024-4671, two n-day vulnerabilities in Google Chrome. Lecigne said APT29’s CVE-2024-5274 exploit was a slightly modified version of the one NSO Group used in May 2024 when it was still a zero-day. The exploit for CVE-2024-4671, meanwhile, contained many similarities to CVE-2021-37973, an exploit Intellexa had previously used to evade Chrome sandbox protections.

The timeline of the attacks is illustrated below:

Google TAG

As noted earlier, it’s unclear how APT29 would have obtained the exploits. Possibilities include: malicious insiders at the CSVs or brokers who worked with the CSVs, hacks that stole the code, or outright purchases. Both companies defend their business by promising to sell exploits only to governments of countries deemed to have good world standing. The evidence unearthed by TAG suggests that despite those assurances, the exploits are finding their way into the hands of government-backed hacking groups.

“While we are uncertain how suspected APT29 actors acquired these exploits, our research underscores the extent to which exploits first developed by the commercial surveillance industry are proliferated to dangerous threat actors,” Lecigne wrote.