After China announced earlier this month that it is suspending international adoptions, Maze Felix, a 28-year-old Chinese adoptee, said they were struck with a heady mix of “anger, relief, grief, confusion — all of it.”

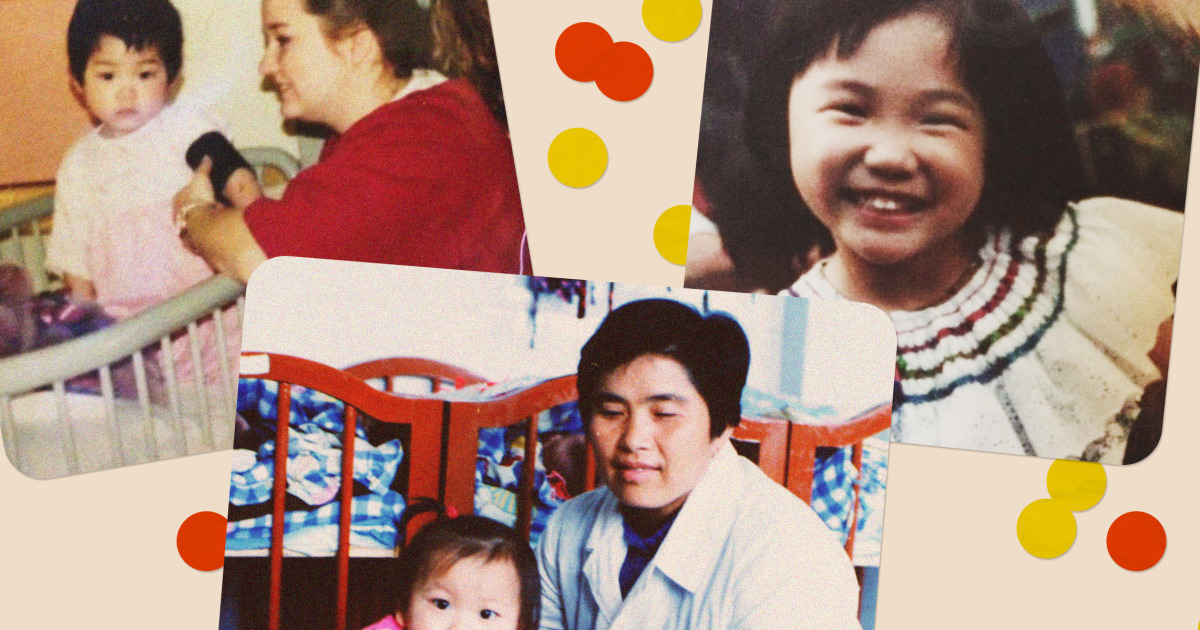

Felix, who uses they/them pronouns, is among the more than 80,000 children who were adopted from China to the U.S. in the past three decades. They were adopted at the age of 2 by parents in Cleveland. And they’re not alone. From feeling relief that relinquished children can now maintain their birth cultures to mourning the end of a program that was central to their own experiences, Chinese adoptees say the new policy has only made an already-complicated experience feel even more complex.

Grace Newton, an adoption researcher and the author of the adoption-focused Red Thread Broken blog, told NBC News that regardless of whether adoptees feel positively or otherwise about the development, “there’s more to it than just that.”

“The feeling is just this mismatch,” Newton said. “How could this massive thing that has influenced so many parts of our life just simply be over on a policy level, when it can never really be over for us on a personal level?”

But given the range of opinions, ultimately it’s been important for many adoptees to find connection among those with their shared experiences, Newton argued.

“We’re a group that will ‘go extinct,’” said Newton, a Chinese adoptee herself. “With that, it feels even more important to find each other and be in community with each other.”

At a press conference in early September, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning confirmed that international adoptions would no longer continue, “in line with the spirit of relevant international covenants.” Exceptions, she said, will be made for foreigners adopting the children or stepchildren of blood relatives in China, up to the third degree of kinship.

It comes after China greenlit international adoption in 1992, leading to roughly 160,000 Chinese children being adopted to other countries, with half going to the U.S. But in the past few years, these adoptions have slowed significantly. During the height of the pandemic in 2020, China suspended adoptions altogether, and no children were adopted to the U.S. for the next two years. But they resumed, with the U.S. consulate issuing 16 visas for adoptions from China between October 2022 and September 2023.

The slowed international adoption coincides with a 2016 reversal of China’s one-child policy, which limited each Chinese family to one child in order to control population growth. In recent years, the country has also struggled with a massive decline in birth rates, signaling major economic and political challenges ahead. In an effort to course-correct, China turned to a “three-child policy” in 2021. And local governments have announced incentives including tax deductions, longer maternity leave and housing subsidies. However, a report by the Beijing-based Yuwa Population Research institute said the subsidies have either been insufficient or just not implemented due to a lack of funding. And for two years in a row, the country’s population has continued to drop.

Katelyn Monaco, a 25-year-old adoptee based in Quincy, Massachusetts, said the new rule stirred up reflections on the one-child policy, a critical backdrop to the development. The policy led to tens of thousands of baby girls and children with disabilities landing in the country’s social welfare system. It was also the policy under which Monaco said she was adopted, and it’s been difficult “knowing that that’s the end of people who may have similar experiences as me.”

But Monaco said she also sees positives, optimistic that the new change could help provide children in orphanages a chance to remain with their birth culture, country and heritage. Often, adoptees grieve the separation they experience from their cultures, she said. And those adopted into a family of a different race can often feel ethnically isolated, feelings she said she felt. Monaco pointed out that some adoptees also face legal challenges in securing citizenship, adding an institutional layer to their identity struggles. Currently, adoptees born on or before Feb. 27, 1983, are not given automatic citizenship, according to the Child Citizenship Act.

“For me that was really difficult,” Monaco recalled. “Growing up with a single mom, even though she loved me and she tried her best, she didn’t have the resources or knowledge to help me understand my Chinese heritage.”

For Felix, one of the most troubling aspects of the new rule is its potential impact on records for existing adoptees. Felix, a Los Angeles-based model, actor and sign language interpreter, was adopted from Yangzhou, China. They said they’ve long done DNA tests in an effort to access their old medical records, adoption papers and other documentation. With little clarity on the fate of those documents, Felix and many other Chinese adoptees said they are concerned that any potential for orphanage visits, birth parent searches and other ties to their home country will be abruptly severed.

“I was longing for something that really was never going to happen … potential cultural connection, or cultural reconnection,” Felix said. “My own life feels like there’s less validity because they’re closing a door on this.”

A representative from the Chinese government did not elaborate on how adoptees’ documentation would be handled.

Newton noted that there have been many cases in which records were falsified or contained sparse information. Even so, there’s been individual and collective documentation “that we even existed in China,” she said.

“There’s a huge fear that we as a group are just going to be potentially a footnote in history or not even mentioned at all,” Newton said.

With the door closed on international adoption, Newton emphasized that in order for those currently in Chinese social welfare institutes to thrive in their birth country, they also need more support. She said money that China once funneled into bolstering international adoption should be allocated to strengthen social support for children and individuals with disabilities in the system. And more should be done to disrupt the social stigma around having a disability in the country, she said.

“The situation truly is a little bit more complicated for these kids with intense disabilities, especially with the rising costs of living in China,” Newton said. “A lot of people, even now that the [one-child policy] is over, are intentionally opting to only have one child. The social infrastructure needs to change so that families can afford to keep their child if they have disabilities.”

While people have had a range of reactions to the news, all those who spoke to NBC News underscored that adoptees should be central to discussions on the change of policy, though that has not often been the case. Newton said adoptees are often seen as “perpetual children” whose points of view don’t need to be considered. And speaking to adoptees in activism spaces can feel uncomfortable for many outside the adoptee community when their religious convictions or other widely held beliefs are challenged. There’s also the misconception that adoption is a “one-time event,” rather than an experience processed in waves across a lifetime, Newton said.

“It may not occur to some that we would have thoughts or feelings about it, because our adoption already occurred,” Newton said of the new policy. “It should be ‘over’ for us.”