Few people pay attention to consolidation in the financial services industry until their bank vanishes after it’s gobbled up by another—usually much larger—institution.

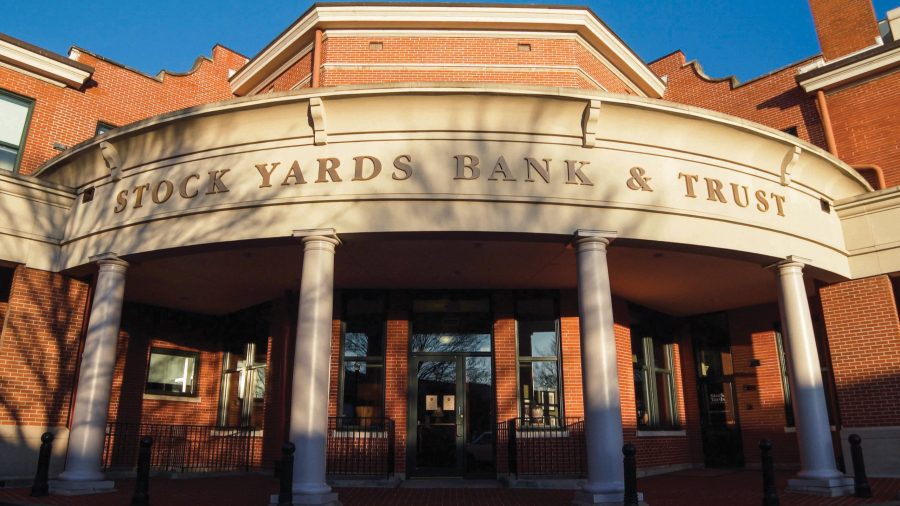

Recent cases in point: The acquisitions in 2021 of Kentucky Bank and in 2022 of Commonwealth Bank and Trust by Louisville’s Stock Yards Bank and Trust, which emerged after those transactions as the largest bank headquartered in the commonwealth, with 72 branches in Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio.

And while national and state trends show a long-running, slow decline in banks and branch numbers, Stock Yards—which traces its history to 1904—is pondering further expansion in Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana.

At the same time, the country’s second-largest financial institution, Bank of America, recently took its first steps in an aggressive growth plan right in Stock Yards’ backyard.

“If you’re coming to Kentucky, there are two markets you have to be in: Lexington and Louisville,” said John Gardner, president of Bank of America in Kentucky and market executive with Merrill Lynch, the BOA investments subsidiary that was acquired in 2008.

BOA, which has had thousands of clients in Kentucky for decades, opened its first brick and mortar locations in Lexington in June 2021, becoming the second nationwide bank to open physical offices in Kentucky. (JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the country with $3.5 trillion in assets, entered the state market in 2004 by acquiring the former Bank One Kentucky as part of a $58 billion multistate deal.) Several of BOA’s new locations feature modern indoor, unmanned kiosks that offer human interaction by video.

Stock Yards is convinced that the acquisition of Commonwealth, with its Louisville branches, is more than adequate to serve that city in terms of physical presence, said Stock Yards CFO Clay Stinnett.

“But we probably don’t have enough branches in some of our newer markets,” said Stinnett, who identified Lexington, Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky as growth targets for his bank.

“You can’t overinvest,” he said, “but that presence and the ‘billboard’ (bank signs) in the community are still vitally important. Folks want to know they have that option of going to a physical branch even if they do 90% of their banking business on the phone or with a PC.”

North Carolina-based Bank of America has had thousands of clients in Kentucky for generations, Gardner points out, but didn’t have a tangible presence until opening the first of four financial centers in Lexington about three years ago. Before deciding to enter the Kentucky market, its expansion marketing team extensively surveyed Kentuckians on whether it was important to have easy access to a bank office.

About 75% of the people quizzed said access to a nearby office was critical, Gardner said. However, when people were asked how often they planned to visit the bank branch, most people responded “never,” he said.

“Their phone is their bank”

Consolidation in the banking industry has slowed in recent years, according to Tasha Stewart, information officer with Kentucky’s Department of Financial Institutions. Branch closures typically are the result of low physical use, indicating customers are being adequately served through other methods.

Banks are investing significant resources into technology that enables them to serve customers through varied and often more convenient means, Stewart said. However, community banks remain cognizant that some Kentuckians may not have ready access to online banking technology and continue serving those individuals by physical branches, interactive teller machines (ITM), automatic teller machines (ATM) and courier services.

Both Stinnett and Gardner emphasized the explosive growth of online banking and the subsequent downturn in walk-in and drive-through traffic at their branches.

“There’s no doubt consumers are using branches less,” Stinnett said. “There are fewer transactions (there) every year and more people are banking on their computer or on the phone. That being said, Stock Yards does continue to expand our branch footprint.”

“For most people today,” Gardner said, “their phone is their bank and as a result of that, the amount of traffic that’s actually taking place inside a banking center is going down. They are very expensive to maintain, and they represent a physical asset that’s on the bank’s books.”

In an aggressive effort to broadcast its brand in the state after a 120-year history in the industry, Bank of America is expanding its brick-and-mortar footprint, especially in Louisville, the state’s largest city and its major business hub. The company plans to have five offices open this year and next and is “looking at additional sites,” Gardner said.

When BOA announced Gardner’s appointment in June 2023, the bank said it had plans to open 10 branches in and around Louisville.

The “build it and they will come” approach runs contrary to what BOA did in 2021 and 2022, when it closed about 525 older branches elsewhere in the country and opened half that number of new financial centers. However, that strategy is irrelevant in Kentucky because the bank is doing its best to trumpet its presence in a new market, Gardner said.

Multiple factors propel branch declines

At the national level, the number of banks has been declining year after year despite ongoing new charters, according to a report last year by global data-gathering platform Statista. In 1983, the United States had 14,469 FDIC-insured banks; last year there were 4,135, Statista reported.

In Kentucky, the numbers were less dramatic over that 40-year period.

More than half of the 336 banks that were doing business in 1983 had either closed their doors or been acquired by 2023, when the FDIC said 158 banks were operating in the state. Since 2012, when there were 221 banks in the state, the total has declined 28%, according to the FDIC’s most recent market share report.

Kentucky’s population has grown by just under 4% or 170,000 people over the last decade, and bank deposits—with one exception—have grown every year since at least 2012. Deposits grew 60% to $115 billion. However, the number of physical sites has declined 17% since 2012–from 1,781 branches to 1,479, the FDIC reported.

“Probably the overall decline (in branches) you’re seeing is driven by the bigger banks,” said Stock Yards’ Stinnett. “Longer term, I think some of those banks—due to consolidation years ago—probably had too many branches in a lot of the markets they were in.”

Stinnett said his bank closed about a half dozen in the wake of the Commonwealth acquisition. Because both banks were headquartered in Louisville, Stock Yards and Commonwealth had some locations that were, in effect, bumping up against one another. “We certainly don’t need locations that are within a mile or two of one another,” Stinnett said.

Stock Yards plans to add 12 to 15 locations in markets where it’s expanding. But the pace of new branch construction may slow to one or two offices per year, Stinnett said. Most recently the company opened for business in late April in the Cincinnati suburb of Mason.

Ballard W. Cassady Jr., president/CEO of the Kentucky Bankers Association, said the number of banks in the state has remained fairly constant in recent years despite steep increases in the cost of regulatory compliance.

“There is a virtual tsunami of regulations coming out of Washington on banking all of a sudden, and the cost of keeping up with them is horrendous. It’s tough for the largest banks to keep up with (the regulations), and if they have to, they go out and hire five more lawyers. But if you talk about the average community bank, they can’t do that,” said Cassady, whose organization represents nearly every bank that operates in the state.

Based on conversations with bankers across the state, Cassady said he believes the cost of compliance has been a factor in some decisions to accept buy-out offers.

Cassady said U.S. Rep. Andy Barr, whose 6th District includes Lexington and serves as the chair of the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Monetary Policy, has pushed to curtail regulatory growth and proposed legislation that could lead to the creation of new banks in the state.

The KBA’s top executive said bankers often tell him, “With this barrage of regulations, we don’t have time to be bankers anymore.”