Hong Kong

CNN

—

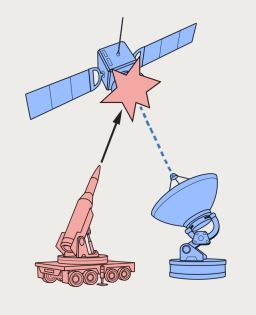

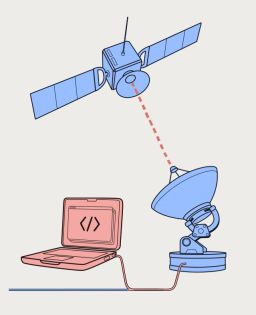

As Russian forces rolled over the Ukraine border in the first moments of their invasion, another, less visible onslaught was already underway – a cyberattack that crippled internet linked to a satellite communications network.

That tech offensive – conducted by Russia an hour before its ground assault began in February 2022 – aimed to disrupt Kyiv’s command and control in the pivotal early moments of the war, Western governments say.

The cyberattack, which hit modems linked to a communication satellite, had far-reaching effects – stalling wind turbines in Germany and cutting the internet for tens of thousands of people and businesses across Europe. Following the attack, Ukraine scrambled for other ways to get online.

For governments and security analysts, the cyberattack underscored how satellites –– which play an increasingly critical role helping militaries position troops, run communications, and launch or detect weapons – can become a key target during war.

As countries and companies build out satellite constellations, a growing number of governments are vying for technology that could disrupt or even destroy adversaries’ assets – not just on land, like Russia’s alleged cyberattack – but in space too.

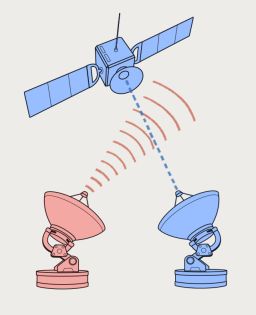

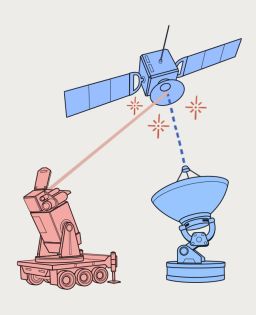

Enter signal jamming and spoofing, high-powered lasers to dazzle imaging sensors, anti-satellite missiles and spacecraft with the capacity to interfere with others in orbit – counterspace technologies that analysts say leading powers like the United States, Russia and China could use to target each other’s satellites.

An extreme example of a potential counterspace weapon was thrown into the spotlight earlier this year when US intelligence suggested, according to CNN reporting, that Russia was attempting to develop a space-based, anti-satellite nuclear weapon – a claim Moscow has denied.

Far from only affecting military-use satellites, such a weapon could have broad, devastating impacts – for example, upending satellites the world relies on to predict the weather and respond to disasters, or even potentially affecting global navigation systems used for everything from banking and cargo shipping to hailing a ride share and ambulance dispatch.

Last week, the US accused Russia of launching a satellite “presumably capable of attacking others in low Earth orbit,” with American officials saying it follows prior Russian satellite launches of likely “counterspace systems” in 2019 and 2022.

Tracking countries’ development of counterspace capabilities is difficult, given their closely guarded nature and the dual use ambiguity of many space technologies.

Both Russia and China have advanced their development of tech that could be used for such purposes in recent years, while the US builds on related space research and capabilities, according to experts and open-source reports.

Development of counterspace technologies is playing out amid a new era of focus on space – where the US and China are competing to put astronauts on the moon and build research bases there and advances in satellite launch technology mean a growing number of actors, including US adversaries like North Korea and Iran, are putting assets in orbit.

And as geopolitical rivalries mount on Earth, experts say Beijing and Moscow are increasingly interested in finding ways to deny the US – as the country with the most ground-based capabilities linked to space – the ability to use them.

The idea of weapons aimed at or positioned in space remains highly controversial, but it isn’t new.

Decades ago, the US and the Soviet Union vied for technologies to knock-out each other’s satellites, with Russia’s 1957 launch of Sputnik – the world’s first artificial satellite – quickly followed by US counterspace tests.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, America has become the pre-eminent power when it comes to capabilities in space linked to conducting military operations on Earth, analysts say – a strength Russia and China have hoped to turn against it to even the battlefield.

“Developing counterspace capabilities such as (anti-satellite) weapons provides a means to disrupt your adversary’s space-based capabilities, whether it is communication, navigation, or command and control systems and logistics networks that rely on space-based systems,” said Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, director of the Center for Security, Strategy & Technology at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi.

“Denying the US any advantage it may have from the use of space in a conventional military conflict is what is driving Russia and China in terms of their capability development and strategies,” she said.

To this end, Russia is believed to have dusted off Cold War-era anti-satellite research programs, such as for the development of an “aircraft-borne laser system” to disrupt imagery reconnaissance satellites, according to an annual report by the independent US-based Secure World Foundation (SWF) released in March.

New evidence suggests Russia may also be working to expand on its ground-based electronic warfare capabilities with the development of space-based technology for jamming satellite signals in orbit, said the report, which is compiled using open-source intelligence.

In recent years, Russia has also launched spacecraft that appear able to surveil foreign satellites – with the high velocity of two of these devices and suggestions others were able to release aerosols indicating they could be weapons tests, according to SWF.

China announced its own counterspace ambitions in 2007 when it launched a missile some 500 miles into space to take down one of its own aging weather satellites. The move broke a decades-long, post-Cold War lull in such destructive, “direct ascent” anti-satellite missile testing, and was followed by similar operations from the US, India and Russia.

Since then, China is believed by analysts to have conducted multiple, nondestructive missile tests that could advance its ability to target satellites. The most recent of those was last April, according to SWF, though, like others, that was described by Beijing as a missile intercept technology test.

China is also believed by the US Space Force to be “developing jammers to target a wide range of satellite communications” and to have “multiple ground-based laser systems.”

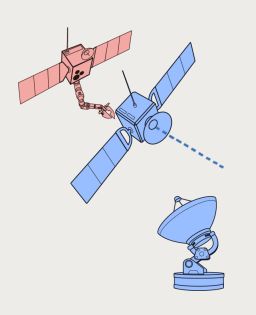

Other Chinese operations in space are difficult to explicitly classify as weapons research but could have a military purpose, experts say. Those include satellites that can approach or rendezvous with others in orbit, such as for support and maintenance purposes, like the Shiyan-7, launched in 2013 and likely equipped with a robotic arm.

There is suggestion from within China of the potential dual use of such technology. In a 2021 state media interview, Zang Jihui, a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) engineer, described China’s experiments with a satellite “equipped with a robotic arm, able to change orbit and conduct all-round detection of other satellites” as part of its “anti-satellite capabilities.”

Beijing included safeguarding its “security interests in outer space” as among its national defense goals in a 2019 white paper, but has long said it stands “for the peaceful use of outer space” and opposes an arms race there. SWF says there is no confirmed public evidence of China using counterspace capabilities against any military targets.

Russia has also said it opposes weapons in space. Both countries in recent years have established military forces dedicated to aerospace, as has the US, which launched its Space Force in 2019 as the first new military branch since 1947.

US officials have described America as a leader in advancing the “responsible and peaceful use” of outer space. And given its reliance on space for its defense, experts say the US military has the most at stake when it comes to ensuring countries don’t use technologies against satellites there – one reason analysts say the US policy community has long shunned placing weapons in space.

Among all nations, only non-destructive capabilities like signals jamming have been actively used against satellites in current military operations, according to SWF.

Since it took down one of its own malfunctioning satellites with a missile in 2008 after China’s test, Washington has pledged to no longer conduct such destructive, direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tests, which can generate dangerous space debris, and is not believed to have an operational program for such capabilities.

It also doesn’t have an acknowledged operational program to target satellites from within orbit using other satellites or spacecraft, though it could likely quickly field one in the future, according to SWF.

That’s because the US has done extensive non-offensive testing of technologies to approach and rendezvous with satellites, including close approaches of its own military satellites and several Russian and Chinese military satellites, SWF says.

The US only has one acknowledged, operational counterspace system – electronic warfare capabilities to interfere with satellite signals – and its army is widely seen to have advanced abilities to jam communications and capabilities to interfere with certain navigation satellites. It also has considerable research on ground-based lasers that could be used to dazzle or blind imaging satellites, according to SWF, which says there’s no indication those have become operational.

Speaking in Washington in November, US Chief of Space Operations Gen. Chance Saltzman explained why the US felt it needed to be able to counter other countries’ space capabilities. He pointed to what he described as a “kill web” strategy used by China’s PLA to enhance the range and accuracy of its weapons within the strategically important “second island chain,” running from Japan to Guam.

“That is all a space-enabled capability,” Saltzman said.

And should Beijing decide to use those weapons, “We have to be able to deny (China) access to the information to break that kill chain so that our joint forces are not immediately in target and in range inside the second island chain,” he said.

Meanwhile, concerns about potential adversaries’ space activities have pushed US allies, including France and Australia, to seek counterspace abilities – often non-destructive ways to interfere with enemy satellites, known as “soft-kill” capabilities, such as lasers to disrupt surveillance and jamming.

Israel has also said it used GPS jamming in its war in Gaza to “neutralize” threats, likely ground-based efforts to avert missiles that reach their target using GPS tracking.

More broadly, there has been a trend toward shorter-term-impact measures like jamming, spoofing and cyberattacks that don’t permanently damage or destroy a target, according to Juliana Suess, a research fellow for space security at London-based defense think tank RUSI.

“(Actors) don’t need to invest a whole lot of money into manufacturing these big sci-fi sounding anti-satellite weapons – they can just disrupt a whole network through a cyberattack,” she said.

More than 7,500 operational satellites are orbiting the Earth, according to the most recent figures from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) in May 2023.

Of those satellites, more than 5,000 were US-owned, with most of them commercial. Nearest competitor China – which has been increasing its satellite launches – had 628, followed by Russia with fewer than 200, according to UCS.

Since it invaded Ukraine, Moscow has accused the West of using commercial satellite systems for military purposes and warned that “quasi-civil infrastructure may become a legitimate target for retaliation.”

Russia has also been accused of mounting cyberattacks against the largest commercial satellite constellation, American company SpaceX’s Starlink, which has been an asset for the Ukrainian military.

When it comes to allegations of developing a nuclear space-based weapon, Moscow has slammed the West as attempting to “assign to us a certain plan of action which we do not have.”

A nuclear weapon in space would be a potential last-resort option – or hanging sword – for its potential to wipe out a wide swath of satellites, albeit indiscriminately.

If Russia is developing such a weapon, its concerns about American constellations like Starlink that have shown military utility are “likely a key motivating factor,” according to Tong Zhao, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace think tank in Washington.

One reason is that as satellite constellations proliferate – aided by advances that have made launches in low Earth orbit (no more than 1,200 miles above the planet) cheaper and easier – it could be difficult for an attacker to cause an impact by simply targeting a single satellite.

By contrast, “employment of such (nuclear) weapons in space could wipe out large satellite constellations, potentially creating long-lasting debris and radioactive remnants that render orbits unusable for military and civilian purposes,” Zhao said. That, he added, could also inflict “an inconceivable setback on the preservation of space as a common domain for future human development.”

Chinese scientists have expressed concern about a potential national security risk of Starlink, with a group writing in the peer-reviewed domestic publication “Modern Defense Technology” in 2022 that “a combination of soft and hard kill methods should be adopted to incapacitate some Starlink satellites functioning abnormally and destroy the constellation’s operating system.”

It’s unclear whether this view reflects thinking within the Chinese government.

Chinese researchers have also considered the ramifications of nuclear detonation in space, with a separate group at a nuclear technology institute publishing research last year on computer simulations of the impact of such blasts at different altitudes, in which they noted there could be potential effects on satellites and other aircraft.

Nuclear weapons already have a controversial history linked to space.

America’s 1962 Starfish Prime nuclear test some 250 miles over Earth damaged at least a third of the 24 satellites operating around that time, according to military documents. It also knocked out powerlines in Hawaii and turned the sky above it a violent shade of orange for hours. The test, launched from Earth, was part of series to evaluate the effect of such explosions, including against ballistic missiles.

Five years later, countries concerned about the heating space race and nuclear standoffs banned the stationing of weapons of mass destruction in space with the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which doesn’t explicitly ban conventional weapons in orbit or missiles launched from Earth.

Though decades old, experts say that treaty – which affirms that space should be used for the benefit of all countries and is endorsed by Washington, Beijing and Moscow – remains a bedrock for a domain that lacks extensive international norms to ensure peace.

Its tenets may be more relevant now than ever – but potentially under greater threat amid a new focus on military and space.

Last month, Russia vetoed an effort in the United Nations Security Council led by the US and Japan to reaffirm the Outer Space Treaty principles, including the obligation not to place nuclear weapons in space. The resolution would have been the council’s first on outer space and was supported by all other members besides China, which abstained.

Instead, China and Russia, which have long worked together to shape rules around weapons in outer space, pushed for that resolution to be broadened to ban the placement of any weapons in space.

Using language that appeared to target the US, it called on “all states, and above all those with major space capabilities” to prevent the “threat or use of force” in space. A second draft resolution backed by Russia that included that amendment, was rejected by the council last week, with the US calling it “disingenuous.”

Any future efforts to agree on rules for space face a complicated outlook, experts say.

For example, placement in space of a nuclear weapon like the one Russia is reportedly considering would have far-reaching implications on how space is used – and how weapons are controlled, according to RUSI’s Suess.

“If the Outer Space Treaty was broken in such a way, it would make it even harder to imagine where multilateral efforts can go from here,” she said.