Public comments for the latest iteration of the cyber incident reporting mandate for critical infrastructure reveal an industry that wants a scaled-back version of what is arguably the Biden administration’s most significant cyber regulation.

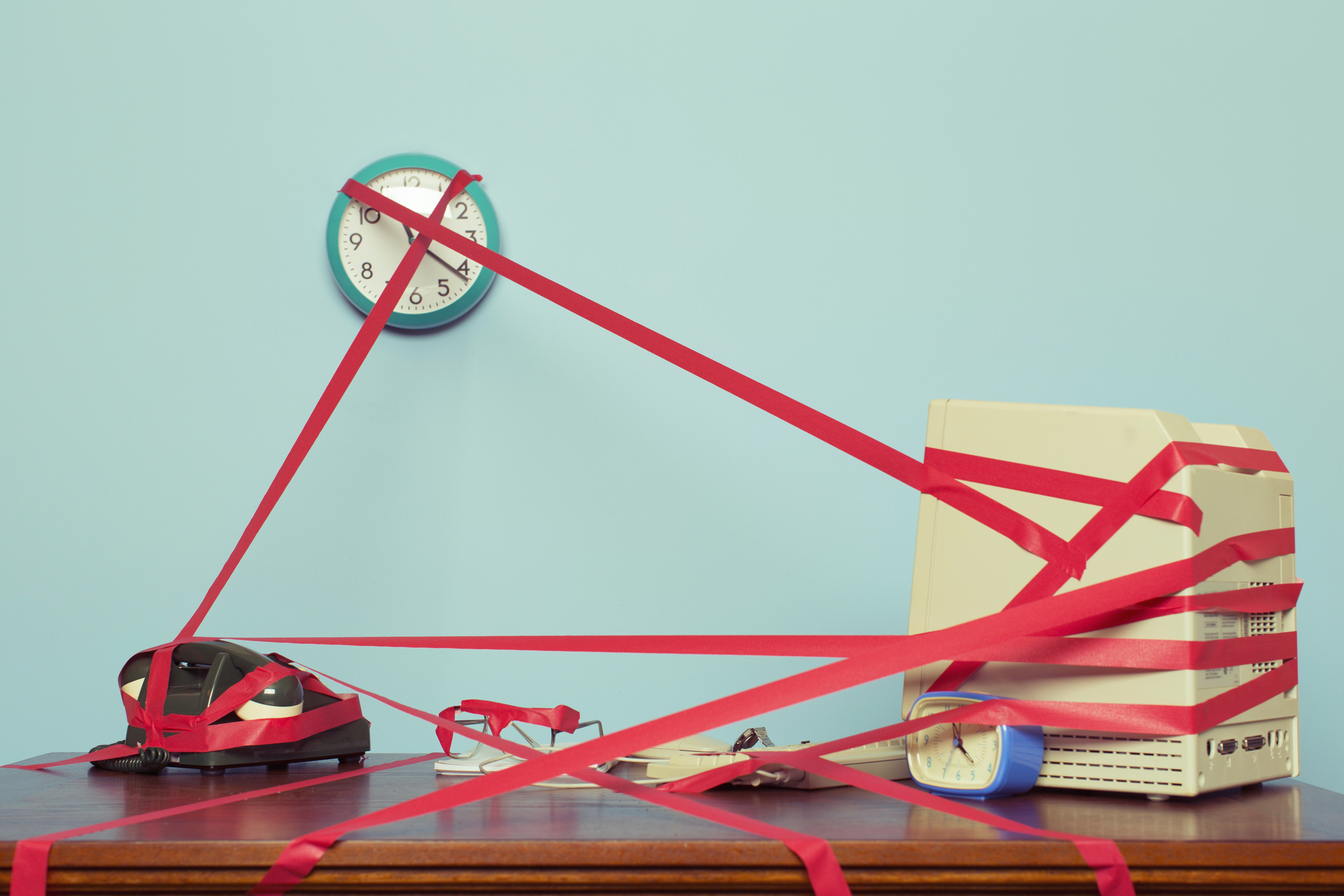

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency will be spending the next few months going over comments from critical infrastructure owners and operators, industry trade groups, cybersecurity companies, and other interested parties after comments for the proposed rule ended Wednesday. The cyber incident reporting law, which is aimed at gaining more information on the threat landscape, comes with the acknowledgement that the defensive posture around cyberattacks against critical infrastructure amounts to reliance on a hodgepodge of state laws, sector-specific regulations, voluntary reporting, and differing levels of access from cybersecurity firms.

The Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act of 2022 (CIRCIA) also may be one of the last landmark federal regulations for critical infrastructure following the Supreme Court’s Chevron decision. Experts have noted that the ruling might encourage legal challenges to new regulations, a tactic that already eliminated cybersecurity audits from the Environmental Protection Agency’s water sanitation surveys.

CIRCIA requires that select critical infrastructure owners and operators report substantial cyber incidents and ransomware payments to CISA within 24 hours. Initial reactions to the cyber reporting law and the subsequent rulemaking process include industry and members of Congress calling for dialed down expectations, clearer definitions, and a more limited scope. The submitted comments were no different. Here are some of the top areas to watch going forward:

Defining a cyber incident

Industry lawyers did not think the 447-page proposed ruling was detailed enough, particularly when it came to what is defined as a cyber incident. Multiple comments asked for specific, clearly defined terms for what is considered a “substantial cyber incident,” including a list of potential exclusions — with some asking for specifics based on sector.

Comments also noted that an overabundance of reports could overwhelm CISA’s resources, leading to little benefit for both the federal government and private sector. The Information Technology Industry Council said that the wide scope of a “cyber incident” could bombard the agency with “irrelevant data,” though CISA officials say they believe current technology can digest the estimated 25,000 reports per year.

The City of Dallas, meanwhile, suggested eliminating part of the law that requires the reporting of ransomware payments. Dallas asked for no “obligation to disclose sensitive payment information” and suggested that fears of “reputational damage and financial scrutiny” could limit a “culture of cooperation and openness.”

Who should report?

Another frequent concern is which organizations are required to report incidents. CISA proposed following some of the sector-specific guidelines for critical infrastructure and adhering to a system that uses a federal measurement for what is considered a small business.

However, many groups commenting also wanted additional details and exceptions from the rule. The National Chicken Council and the Meat Institute argued that CISA should change the small business threshold, as food and agriculture businesses don’t fall neatly into one area. Additionally, not all companies will be aware of the new law. CISA noted in the proposed rule that it has no plans to alert every organization that might fall onto that list, citing scale.

Similarly, trade groups like the National Retail Federation said the businesses they represent should be excluded entirely, as retail cyberattacks rarely impact national security and public safety. The Enterprise Cloud Coalition also expressed concern that the proposal could require third-party service providers to report an incident “when such providers have limited information on the customer impacts.”

Lawmakers previously criticized CISA’s rule, which they consider too wide in scope. Rep. Yvette Clarke, a New York Democrat, the former chair of the House Homeland Security cyber subcommittee and the sponsor of the bill, said during a recent House hearing that CISA’s rulemaking went too far.

Carrot and stick

While the vast majority of critical infrastructure sectors may be privately owned, many lack the needed resources to have a cyber specialist on the ground to implement the requirements. The American Council on Education noted that many institutions don’t have the funds to follow the proposed rules. The council also noted that due the lack of “substantial engagement” on the rules or on the implementation of CIRCIA, the government should narrow covered entities under higher education.

It’s unclear what — if any — consequences businesses will face for not submitting a report. The American Hospital Association said that the potential penalty for not complying with the law could be “vague and potentially severe” while also punishing victims.

The American Medical Association noted that CISA should provide additional resources both for organizations that are impacted and required to report and for smaller practices that fall below the threshold. The AMA said “financial incentives are most effective when framed as a positive stimulus, as opposed to a penalty.”

Harmonization

One of the remits CISA is required to complete is harmonizing the slew of cyber reporting rules. That’s because the law is also meant to eliminate redundancies, red tape built as agencies and regulators separately created cyber reporting rules. The law is also intended to combat increased costs of cyber defenses.

Multiple comments from energy companies — including the Edison Electric Institute, a trade group representing investment-owned utilities, and oil and natural gas trade associations — noted that they already have existing regulations that should take precedence. The Electric Power Supply Association, meanwhile, wrote that some cyber reporting rules issued by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation call for quicker reporting times than CIRCIA.

Additionally, USTelecom – The Broadband Association said that telecommunication members are concerned about the “substantial resources” needed to “comply with the patchwork of incident reporting requirements.” The association warned that without streamlining ways to report, they expect the industry to adopt a just-in-case attitude and over-report incidents that could “strain government resources and be counterproductive for both sides of the public-private partnership.”

Security and sharing

One of the more cynical — if not historically accurate — trends in the comments was a general questioning of whether the federal government will share information. Comments expressed concern that the government still has an issue with information sharing and questioned whether it could safeguard sensitive information.

The Maritime Transportation System Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MTS-ISAC) expressed frustration at the proposal, writing that the federal government regularly falls victim to “cyber incidents that have leaked more sensitive, classified information” than CISA plans to collect.

The MTS-ISAC also expressed concerns about whether the federal government will share information, noting repeatedly that “there is no stated commitment for CISA to share — only to collect.”

The Virginia Port Authority seemed to agree, noting that several times, the organization learned of incidents through the news rather than through established alerting mechanisms.

“Federal agencies are slow to share information and actionable intelligence with ports directly or through industry sharing and analysis groups in a timely manner,” the VPA said.