PPAs have arguably been the most powerful tool for bringing clean energy into the grid in the US and Europe — but they are in need of a serious makeover if that impact is to continue. A new approach to PPAs is especially urgent to ensure the wave of new power demand from data centers and EVs isn’t met with fossil fuels.

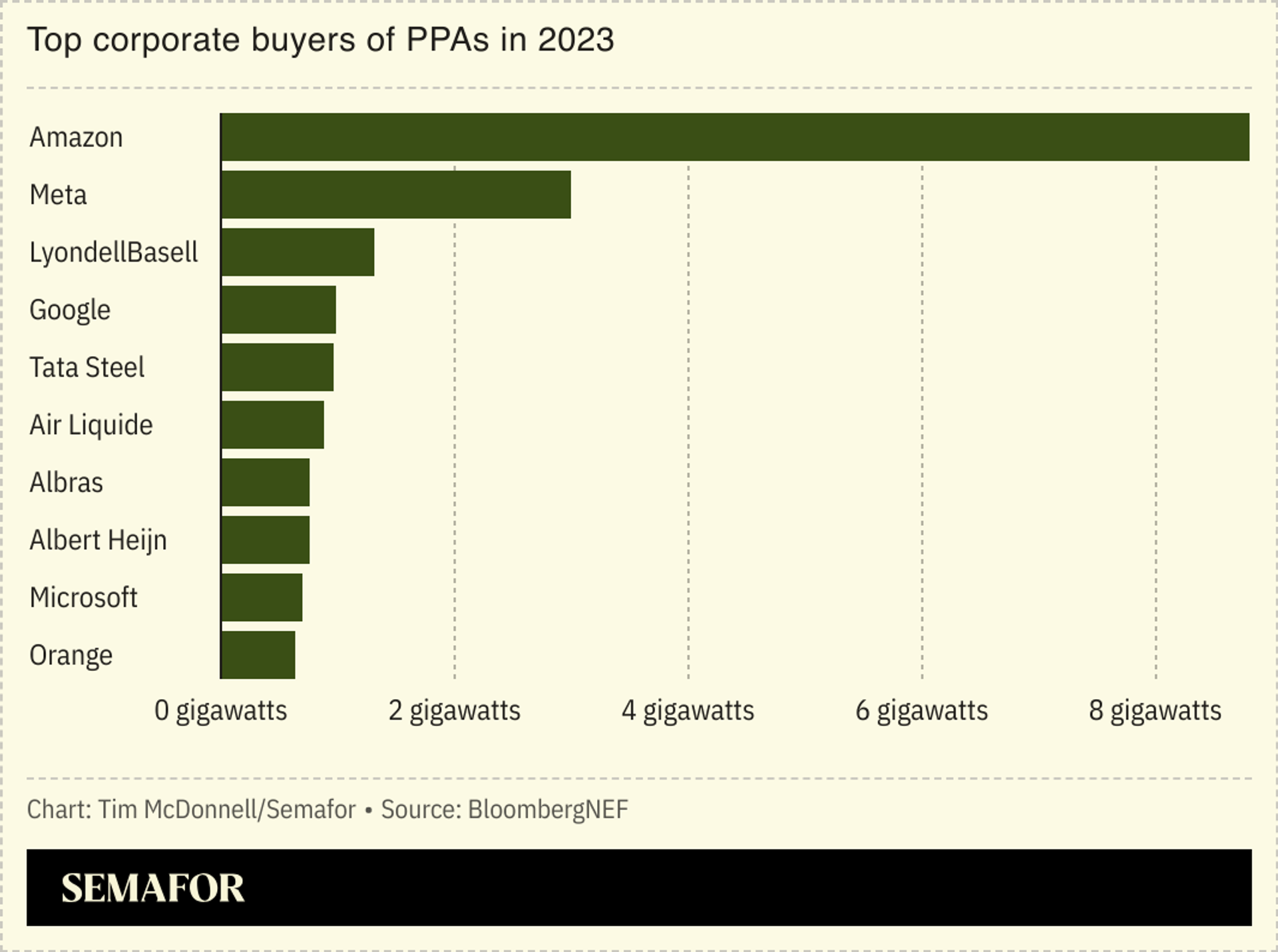

In a typical corporate PPA, a company signs a 15-20 year purchase agreement with a solar or wind farm developer. In most cases, the buyer isn’t actually taking power directly from the plant, but is technically buying only a certificate representing the power’s zero-carbon attributes; the power itself flows into the local grid and can’t be counted against anyone else’s carbon footprint. These deals make new projects bankable that otherwise wouldn’t be, and they’re one of the only ways for a company to jump ahead of whatever its utility is willing or able to do to decarbonize. They are also typically structured so that if the prevailing daily price of power falls below the fixed rate in the PPA, the buying company will get paid back the difference, which for Google and other buyers has become an important side stream of revenue. In 2023, companies globally, mostly in Big Tech, signed a record 46 gigawatts of PPAs, according to BloombergNEF, equivalent to the overall power output of 100 midsize coal plants.

But traditional PPAs are running into a few “serious limitations,” Gollin said. They aren’t available in the half of US states with vertically integrated utilities, where deals that exclude the utility aren’t allowed. It can be a headache, Gollin said, to manage essentially two separate sets of energy bills, from the PPA certificates and the actual power the company is still using from the utility. They often aren’t economic for large, expensive, cutting-edge baseload power projects like geothermal and advanced nuclear. Wind and solar PPA prices are rising in the US because of high inflation rates and supply chain bottlenecks, forcing many developers to renegotiate. And the explosion of PPAs has essentially created a parallel virtual grid, Gollin said, which is a headache for utilities that remain responsible for transmitting power they weren’t involved in planning.

“We don’t want to build an island just for Google, because that’s not going to catalyze the type of change we want to see,” Gollin said.

Google’s “clean transition rate” solves these problems by essentially re-introducing the utility as a middleman. The utility decides what specific mix of climate tech is best, and negotiates a rate large buyers can pay to tap it. Being able to access a lot of advanced clean baseload power will lower by 40% the cost for Google to meet its goal to source 100% of its power from clean sources around the clock by 2030, compared to relying exclusively on intermittent wind and solar, and conventional batteries. And it can push Nevada’s overall grid to be cleaner without raising rates for regular customers. Every gigawatt of clean baseload the utility builds is one less gigawatt of gas generation it would need to build to ensure reliability as demand increases.

The latter, Gollin said, results in “a bunch of stranded assets on the system, and it’s a poor use of money.”