Luis Alvarez

We have already discussed how strong shopping center fundamentals are, given the lack of development in the last 15 years and demand approaching a point of full occupancy. The question I want to address today is – How long can it last?

To address this question, let us first explore the mechanisms that govern the length of a real estate cycle.

The length of a real estate cycle

Real estate is inherently cyclical, as it has internal feedback mechanisms that keep it in check. When a given property type is performing poorly, development of that property type is no longer viable, such that supply declines over time relative to demand. The lower relative supply improves the fundamentals and restores profitability to normal levels.

Similar feedback mechanisms work in the opposite direction when things get a bit too hot. The increased level of profitability incentivizes development, at which point the excess supply cools the fundamental outlook.

The feedback mechanisms (development or lack thereof) act as bumpers to maintain equilibrium. As such, real estate performance usually stays within a certain band of profitability.

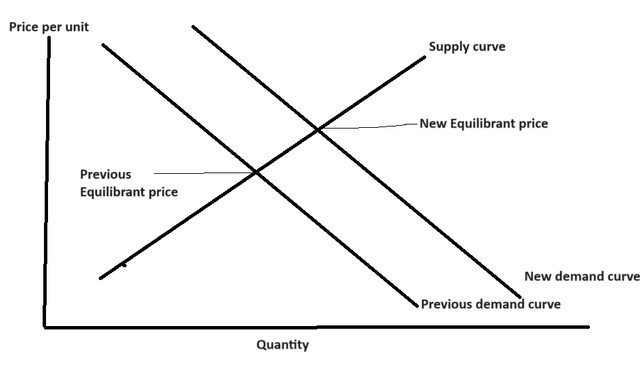

To see these feedback mechanisms in action, we can look at apartments in the last 3 years. Following the pandemic, there was a surge in demand for apartments due to household formation, relative unaffordability of homeownership, and strong jobs. In economic terms, this shifted the demand curve to the right.

At any given price point, more apartment units were demanded. The supply curve was largely unchanged, but with the shift in the demand curve, the now higher equilibrated price incentivizes more development.

Developers came in aggressively, building as much as 10% of existing supply in some submarkets. This new development was the feedback mechanism that kept the market in check.

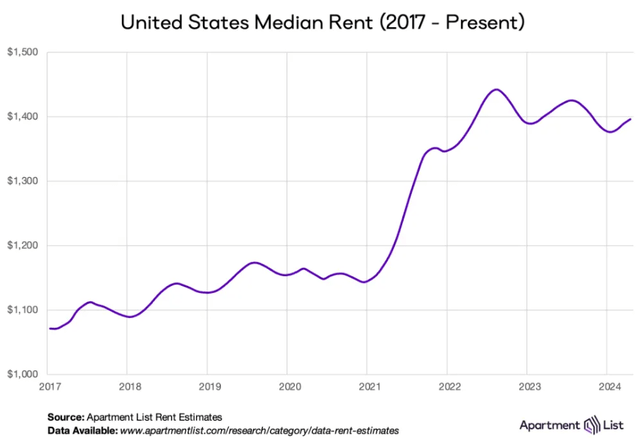

You can also see it play out in rent terms.

The post-pandemic demand boom increased rents from below $1200 to over $1400. Then the supply came in starting in 2023 and continuing through mid-2025, which moderated rent growth.

Equilibrium in apartments has been restored, and it is now in a relatively normal environment with fairly average forward expected growth in profitability.

So how does this relate to shopping centers?

In shopping centers there has been almost no new development for the last 15 years and demand has finally caught up to and surpassed existing supply.

Just as apartments had a 20% rental rate surge in 2021-2022, shopping centers are currently experiencing rental rate increases of 20%-40%. This level of rent growth would usually trigger the development feedback mechanism such that new supply would come in, and the market would normalize.

If that were the case, shopping center rental rate growth would normalize, and forward growth rates would return to average. I posit that the feedback mechanism will not work in shopping centers, such that there is a very long runway of outsized growth. I believe it will be a golden age of shopping centers.

The shopping center golden age

The logic is as follows:

The required cap rate to make development worth the risk given the higher interest rate environment is at least 8%. Presently, rents are so low and construction costs are so high that development of shopping centers is not even close to being viable except in unique circumstances.

Even with the 20%-40% increase in rental rates, the NOI yield of new development does not exceed the required rate of return. As such, rental rates will have to get much higher before the feedback mechanism kicks in.

Here are the numbers that lead me to this conclusion:

- Average cost to build shopping centers of equivalent quality and location is between $300 and $500 per foot.

- NOI margins vary, but are often around 70%.

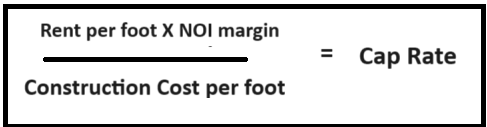

From these numbers, we can calculate the amount of rent per foot required to achieve an 8% development yield.

2nd Market Capital

For the lower end product, costing $300 per foot to build, it would need $24 per foot of NOI to achieve an 8% cap rate. Using the 70% NOI margin, this would mean rent per foot of $34.28.

Prime locations costing closer to $500 per foot to develop would need about $57 per foot in rent to achieve an 8% NOI cap rate.

So, development becomes viable as rents approach $34-$57 per foot, depending on location and level of luxury.

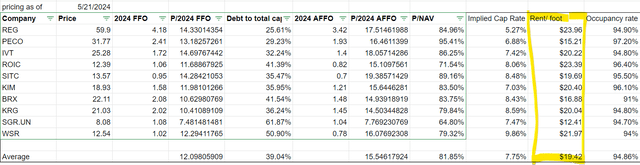

Now, let us contrast that with where rents are today.

The average shopping center REIT charges rent per square foot of $19.42. Note that REITs tend to own the top quartile of real estate, so the REIT average is well above the national average.

Rental rates are about half of where they need to be for development to become a real threat. This means the equilibrating feedback mechanism of development that usually kicks in when rental rates rise 20%+ is not there.

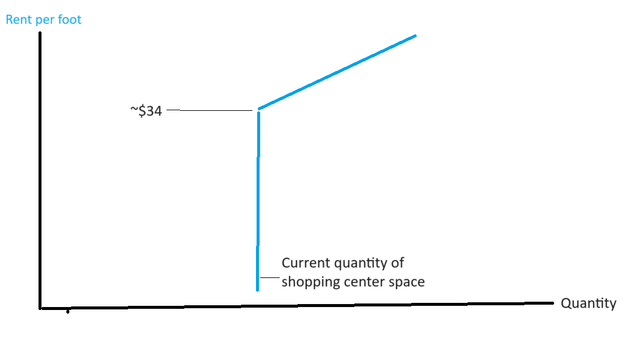

The supply curve for shopping centers looks more like this:

So when the demand curve is shifting to the right as it is now and raising the equilibrating rental rate, supply is unlikely to increase until rental rates go much further.

As such, assuming demand holds up, shopping centers could have substantially more rental rate growth before feedback mechanisms stop the growth.

To me, this looks like a golden age for shopping centers.

How did shopping centers get here?

Achieving such a state did not happen without pain. Shopping centers have largely been struggling since the financial crisis. They were overbuilt in 2005-2007, and then the weak economy of the financial crisis took demand well below where it needed to be for the level of existing supply.

As the economy recovered, demand started to come back, but then they were faced with a new threat with E-commerce appearing in a big way. With E-commerce gobbling up a significant portion of sales that would have otherwise gone to brick and mortar, demand remained below the existing level of supply. Thus, even without new shopping centers being built, shopping centers were oversupplied for much of the 2008-2021 period.

Due to low occupancy of the oversupply, rental rates failed to go up in pace with inflation of construction costs. Rental rates have remained at levels that were appropriate for construction costs, closer to $150-$200 per foot.

However, demand began flowing in 2022 and really picked up through now, causing increasing upward pressure on rental rates. Occupancy for shopping center REITs has reached 94.8%, which is very close to full occupancy, as frictional vacancy will generally be at least 3%.

Full occupancy is a critical threshold, as it is the point at which tenants have to start competing with one another to get space. It is similar to the housing market when 12 potential buyers are bidding on the same home. In such an environment, rental rates can rise quickly. So far, this has resulted in:

The above numbers are new lease rates compared to what the previous tenant was paying.

In housing, home prices are well above construction costs, so home builders are responding with ample development volume. This feedback will normalize home prices. They might remain high, but the pace of rate increase should return to normal.

Shopping centers are uninhibited in their rent increases because development just isn’t viable at current rental rates. Thus, rents could go up another 50%+ before the feedback loop kicks in and restores equilibrium.

Incumbent shopping centers are the winning section of the vertical

Without developers coming in to share in the profits, existing shopping centers are positioned to capture the benefits of higher rental rates.

While development cap rates are too low to be viable, redevelopment of existing space is proving quite lucrative. Many of the REITs have reported IRRs in the 20s on redevelopment of existing space. Capex was often foregone during the challenging years for the sector, so there is quite a bit of investment needed.

Another method by which value can be realized is through the sale of assets. Private equity wants to get in on the sector and with development largely out of the question, this means paying up for standing assets. J. P. Morgan REIT (a private REIT) just bought a shopping center for $48 million, or roughly $480 per square foot.

Note that this particular asset was in Queens, so its replacement cost is likely even higher than that.

Over the coming months and years, I think rental rates will continue to rise significantly and there will be many buyouts of undervalued REITs. The shopping center REIT sector is trading at an average enterprise value per square foot of $233. The asset value is closer to $350. We are heavily overweight the sector.