A jury will soon weigh Donald Trump’s fate in the New York hush-money trial that could culminate with him becoming the first US president to be convicted of a crime.

Meanwhile, he faces three other criminal indictments for withholding classified documents in Florida and attempting to overturn the 2020 election in two separate cases in Washington DC and Fulton County, Georgia. And that’s all while he remains hot on the trail of another stint in the White House.

The ex-commander-in-chief — already the first in American history to be impeached twice — is also battling a number of other lawsuits relating to his business practices and personal history.

He denies all possible charges and is arguing that, in any case, a president should be granted absolute immunity from prosecution to enable them to execute difficult decisions in the Oval Office without fear of future reprisals, a matter on which the US Supreme Court could soon rule.

Despite this blizzard of controversy, conservative voters appear largely persuaded by Mr Trump’s baseless “political persecution” narrative, which he has gleefully used to fundraise for his campaign.

The candidate has insisted he will remain in the race for the presidency whatever the outcome of the criminal cases against him and, so far, his strategy of delay, delay, delay appears to be working, with no further trials looking likely before Election Day.

What are the four indictments about?

Mr Trump’s troubles began in April 2023, when he became the first-ever former or current American president to be hit with criminal charges when a New York City grand jury voted to indict him over an alleged $130,000 hush money payment made to the porn star Stormy Daniels just prior to the 2016 election.

He pleaded not guilty to 34 felony counts of falsifying business records in order to the hide the payout to Ms Daniels, allegedly made to suppress her allegation about an extramarital sexual encounter in 2006 that might have cost him valuable support at the polls.

His second indictment followed that June, when Justice Department special counsel Jack Smith handed down federal charges against Mr Trump and his valet, Walt Nauta, with 37 counts related to the unlawful retention of classified documents post-presidency and the obstruction of justice.

A second Trump employee, Carlos De Oliveira, was later also caught up in the case, brought about after the FBI raided his private residence, Mar-a-Lago, in search of boxes of classified documents he had declined to return to the National Archives.

Mr Trump’s third indictment, again courtesy of Mr Smith, occurred in August and pertained to the 2020 election and his role in kickstarting the Capitol riot.

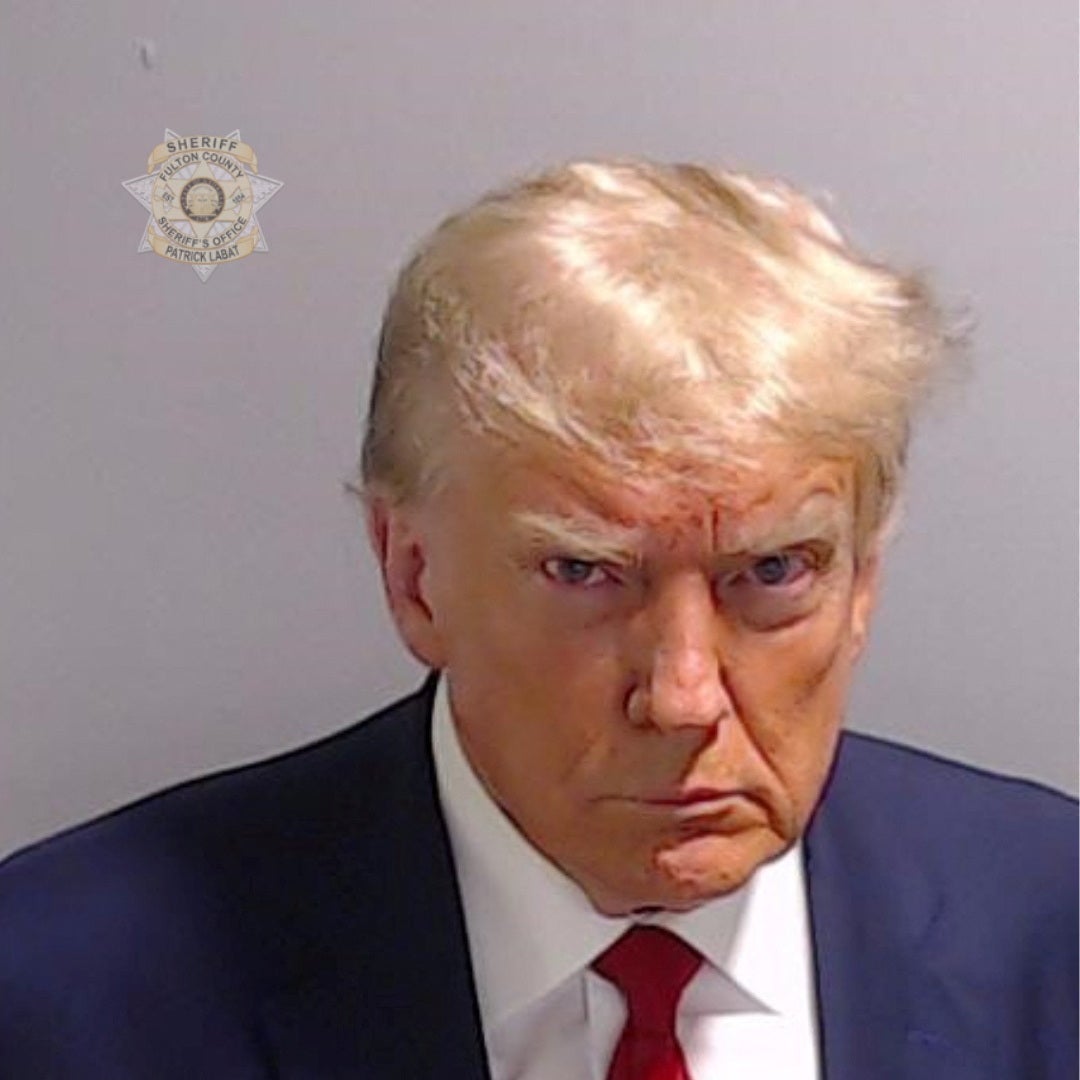

The former president was then indicted for a fourth time in Georgia later that month, this time charged by Fulton County district attorney Fani Willis with 13 counts related to an alleged conspiracy to alter the election result in the swing state in the aftermath of his defeat to Joe Biden.

He was charged alongside 18 other defendants, including Rudy Giuliani, Mark Meadows and Sidney Powell, in an indictment containing a total of 41 counts related to racketeering.

Mr Trump has further been found liable for the sexual abuse and defamation of magazine columnist E Jean Carroll and for fraud over the Trump Organization’s systematic inflation of the value of its assets to secure favourable terms from lenders, which yielded a $464m judgement against him earlier this year.

So can he still run for president?

There are no explicit restrictions in the US Constitution to prevent anyone under indictment or convicted of a crime – or even currently serving prison time, for that matter – from running for or winning the presidency.

That said, a clause contained within the 14th Amendment was enough to convince the Colorado Supreme Court and Maine’s secretary of state that Mr Trump should be removed from ballot papers over his part in inciting the events of January 6.

However, the former president was able to successfully appeal both of those decisions and the matter ended up in the conservative-majority Supreme Court. There, the justices ignored the question of whether or not he had engaged in an insurrection but determined unanimously that only Congress could disqualify a candidate for federal office.

Thanks to the success of Mr Trump’s delaying tactics, none of the other indictments brought against him currently have a trial date set in stone, with Judge Tanya Chutkan in DC and Judge Aileen Cannon in Florida withdrawing the dates they had originally set, so the Manhattan hush money trial could be his last court engagement before 5 November.

But even if the tectonic plates were to suddenly shift and one of the trials did come to pass in speedy fashion and secure a miraculous conviction, Mr Trump would still be free to run the entirety of his campaign from a prison cell.

What is far less clear is what would happen if he were to win.

Just as there are no restrictions in the Constitution on a person running while under indictment, there is no explanation of what should occur if they go on to win, not even an automatic reprieve from prison time.

However, if Mr Trump were to assume the presidency while federal charges were still being litigated, they would likely be dropped because of the Justice Department’s refusal to prosecute a sitting president.

But state-level charges like the ones filed by Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg or Ms Willis would fall outside of any prospective presidential pardoning power.

If the politician were to be convicted on state charges and win the 2024 vote, it would likely lead to a massive legal brawl to determine whether there was a way for him to wriggle out of serving time.

If Mr Trump was unable to avoid that outcome, it would almost certainly lead to his impeachment (for a jaw-dropping third time) or his removal via the 25th Amendment.

There are many duties and trappings of the presidency he would simply be unable to fulfil from a prison cell – the viewing of classified materials, to name just one.

While much remains unknown, the conversations Donald Trump has started with his bid for the presidency under such troubled circumstances have already pushed theoretical constitutional law into much darker places than many experts ever believed they might live to see.

This story was updated on 24 May 2024 to reflect new developments.