Underwater drones adapted to cold Nordic waters, and sensors that listen to the sounds of fish eating. These are some of the AI solutions that could give European sea farmers a boost to compete globally. Researcher Fredrik Gröndahl explains how maching learning is being developed to take on operational challenges and reduce costs in aquaculture, particularly in inaccessible waters far offshore.

In the global seafood market, European aquaculture could expect a boost from AI solutions developed by researchers at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

At the Blue Food research center, KTH researcher Fredrik Gröndahl oversees several projects that harness machine learning to take on operational challenges and reduce costs in aquaculture, particularly in inaccessible waters far offshore.

Seafood farmers incur high costs in hiring the vessels and divers needed to access seaweed beds, which are increasingly being located farther from shore in order to avoid conflict with other coastline uses and property rights.

“We are trying to find ways to be more and more competitive,” says Fredrik Gröndahl, director of the Blue Food Seafood Centre. Several AI projects are in the works, with the aim of boosting competitiveness in the global sea farming industry.

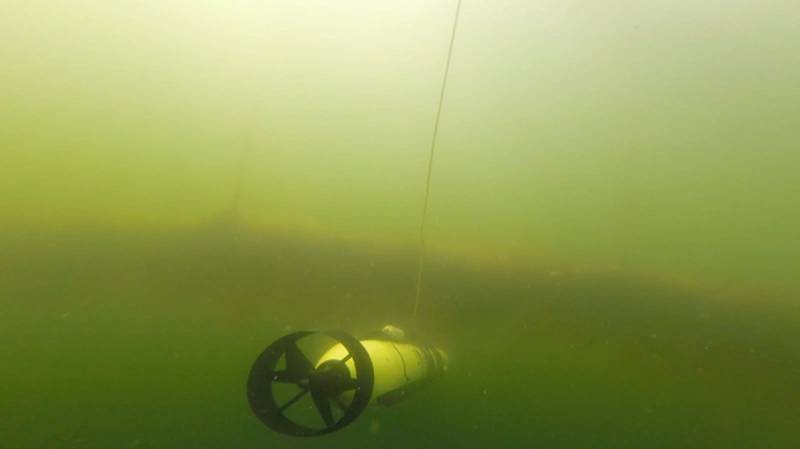

Photo Fredrik Gröndahl

So researchers at KTH have been working on substituting boats and divers with autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that are to be optimized for the colder Nordic waters. These vessels, which are under development at the Swedish Maritime Robotics Center at KTH, are equipped with sonar and algorithms to detect the submerged ropes that seaweeds grow on. Enabled by artificial intelligence they are meant to navigate along these lines, well out of view of their human operators on land.

AI is also being adapted to fish farming. In the oyster beds of Sweden’s west coast, the Skagerrak strait, Blue Food researchers are testing algorithms intended to identify invasive species of oysters from those approved for cultivation in the EU.

The research attracts investment because it offers a realistic way to level the playing field in competition with large-scale sea farming, particularly in China, he says. “I visited a giant seaweed farm in China that had 1,000 hectares of seaweed alone, plus mussels and other fish,” Gröndahl says. “They were very labor intensive, with the work being done mostly by hand. We could never do that in Sweden.

“Labor in Europe is expensive so we have to have machines and automated, optimized systems to be competitive to produce food,” he says.

Machine learning is also being developed to avoid wasting fish feed in enclosed pens. With the help of submerged microphones, the researchers are testing an automated feeding system that listens for the sounds of fish eating. When the sounds subside, the release of feed is shut off. “This can save a huge amount of money for fish farmers, on land or in the sea,” he says.

“You can optimize the feeding so the fish get exactly what they need. Otherwise, if the fish are full the excess feed will sink to the bottom and then we have a problem,” Gröndahl says.

On land, AI also can be used for balance and control of water quality to prevent anoxic death of fish being raised in enclosed systems.

The work also enables synergies with the energy sector, where interest is growing in combining offshore wind parks with seaweed farming. In these kinds of scenarios, sea drones can also be used for more continuous monitoring of windmill and wave energy, which take a beating in the harsh conditions of the ocean. “We are trying to find ways to be more and more competitive,” he says. “Around Europe, whenever we present this underwater robot collaboration, people get very enthusiastic.”

An underwater drone navigates a seaweed bed on Sweden’s west coast.

An underwater drone navigates a seaweed bed on Sweden’s west coast.

Photo: Ivan Stenius