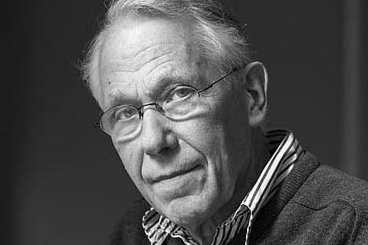

Nicolaas John Habraken, architect, educator, and housing theorist, died on October 21, 2023. As an educator, he left an indelible mark at both the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands (TU/e), where he was the founding dean of architecture, and at MIT, where he served as head of the architecture department from 1975 to 1981 and remained on the faculty until 1990.

Although these two campuses were his primary institutional homes, his influence was much wider, extending to an international network of scholars and practitioners dedicated to flexibility in the design and delivery of housing.

“John Habraken’s focus on change and adaptation in architecture provides an essential model of transformation to both teaching and design,” says Nicholas de Monchaux, head of the MIT Department of Architecture. “And the profound shift in thinking his ideas demand — from a momentary focus on objects to the long-term beauty and resilience of the built environment — is even more relevant today than when John arrived at MIT five decades ago.”

Architect John Dale, who studied with Habraken at MIT, says, “Throughout his life, he invented, investigated, challenged, and inspired — seeking to give design professionals, agencies, developers, and user groups a path to creating long-lasting, adaptable buildings. His theories and methods were realized in thoughtful, visionary projects all over the world.”

Rethinking the methodology of architecture was indeed central to his work, yet another Habraken student, Renee Chow — currently serving as the dean of the College of Environmental Design at the University of California at Berkeley — says, “For me, John was a teacher of values rather than method.”

Born in Bandung, Java, in 1928, Habraken prioritized resident decision-making in the design and use of housing—not a leading concept at the time. As a boy, he had been inspired by the self-built kampung he observed in West Java, in which village residents made major decisions about the size and arrangement of both communal and family living spaces.

When his family relocated to the Netherlands in 1947, he found in studying architecture at the Delft University of Technology that postwar rebuilding efforts excluded occupants’ preferences, offering only standardized apartments. Through his research, writing, and teaching, he inspired multiple generations of architects to study the everyday built environment and the variety of forces that influence its settlement patterns. Only then, he argued, could architects formulate design strategies that could respond to the ways households’ needs change over time.

His first book — “Der Dragers en de Mensen: Het einde van de massawoningbouw,” published in Dutch in 1961 and in English in 1972 as “Supports: An Alternative to Mass Housing” — sought to apply the promise of manufactured building components to support flexibility and user decision-making in residential environments. The book advocated for distinguishing between the design and construction of “supports” and that of “infill.” He defined the former as permanent superstructures and the latter as customizable living units. Separating the design responsibility of those building elements intended to endure from those that benefitted from user input and flexibility, he argued, could enable architects to spend more time consulting with residents and negotiating between the needs of the community and those of the individual household.

The book positioned Habraken to accept the founding director role at the recently formed Stichting Architecten Research (SAR) in the Netherlands, which sought to claim a more robust position for the architecture profession despite the increase in standardized building. Between 1964 and 1990, the SAR’s research output aimed to combine the efficiency of industrial fabrication with the flexibility of user customization.

The prominent role of research within the SAR’s activities recommended Habraken for another leadership post, this time in education. When the Eindhoven University of Technology was established in 1956, there was debate as to whether architecture belonged among the degree programs. But his commitment to research overcame skeptics, and Habraken served as the founding dean of architecture at the TU/e. The pedagogy he advanced there signaled a shift in architectural education away from the monumental architecture that characterized his own education and toward residential environments and the vernacular landscape.

For some students, this curricular focus on practical construction technology, heating, and ventilation systems, and empirical study into optimum dimensions, proved too structured for a creative discipline facing the cultural convulsions of the late 1960s. Habraken remained committed to expanding architectural education, and in 1975 he was named head of MIT’s Department of Architecture, where he remained on the faculty until 1990.

Jan Wampler, who taught with Habraken, says, “He gave MIT a great gift when he came and provided a strong clear direction for the program.” Thijs Bax, a longtime collaborator who succeeded Habraken as dean of architecture at the TU/e, added that his friend always approached the leadership of academic departments as a design challenge in which the structure of interdisciplinary collaboration required both a strong vision and a nimble responsiveness to context.

Habraken is survived by his wife, Marleen; their two children, Julie Habraken of Appeldoorn, Netherlands, and Wouter Habraken of Austin, Texas; and Wouter’s wife, Chandra Roukema, and their daughters, Maya and Phoebe.

Dale and another Habraken mentee, Stephen Kendall, co-edited “The Short Works of John Habraken: Ways of Seeing, Ways of Doing” (Routledge, 2023), which complements both architects’ work in advancing and adapting Habraken’s ideas about how to design flexibility into the built environment, making architecture that can respond to the unique and shifting needs of its users. This book joins Habraken’s significant output of written work, including his magnum opus, “The Structure of the Ordinary” (1998), “Transformations of the Site” (1983), and “Palladio’s Children” (2005).

Habraken’s ideas anticipated current debates about how to center resident experience and enable resident decision-making in the design of housing and how to respect the diversity of households and the ways space needs change over time. His lasting gift to how architecture and urbanism is taught is his exhortation to observe and learn from commonplace environments.

In an exploration of his career’s importance in light of contemporary challenges to deliver more housing while respecting the agency of residents, the article “Mass Support” in Places journal is a companion piece to an exhibition investigating the legacy of the SAR that premiered at the TU/e before being installed at the Spitzer School of Architecture at City College in New York City. Planning for future iterations of this exhibition is currently under way.