The world outside the US is increasingly driving Chinese electric vehicles, scrolling the web on Chinese smartphones and powering their homes with Chinese solar panels.

Since Donald Trump hit Xi Jinping’s government with punitive tariffs in 2018, his push to cut the trade deficit has snowballed into a full-scale bipartisan effort to stop China from becoming the world’s biggest economy and obtaining technology that threatens American military superiority.

Chinese President Xi Jinping. Photographer: Sarah Metssonnier

At a glance, the campaign appears successful. China’s economy is no longer on pace to overtake the US and is actually falling further behind. Its tech giants face difficulty obtaining advanced chips to develop artificial intelligence. And US allies are complying with requests to deny China access to the best chip-making equipment, including one-of-a-kind machines from Netherlands-based ASML Holding NV.

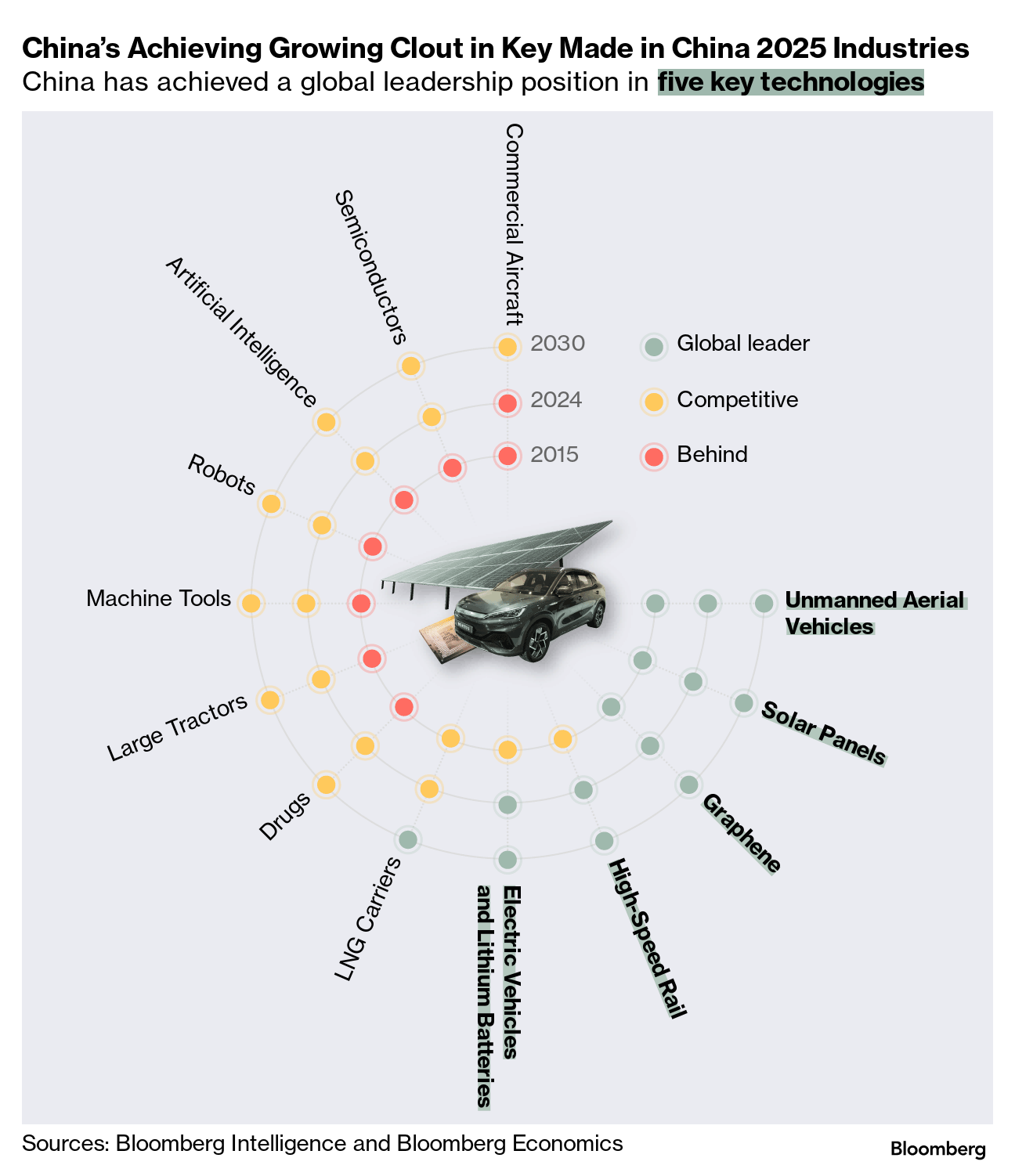

But despite more than six years of US tariffs, export controls and financial sanctions, Xi is making steady progress in positioning China to dominate industries of the future. New research by Bloomberg Economics and Bloomberg Intelligence shows that Made in China 2025 — an industrial policy blueprint unveiled a decade ago to make the nation a leader in emerging technologies — has largely been a success. Of 13 key technologies tracked by Bloomberg researchers, China has achieved a global leadership position in five of them and is catching up fast in seven others.

China’s Achieving Growing Clout in Key Made in China 2025 Industries

China has achieved a global leadership position in

five key technologies

Sources: Bloomberg Intelligence and Bloomberg Economics

That means the world outside the US is increasingly driving Chinese electric vehicles, scrolling the web on Chinese smartphones and powering their homes with Chinese solar panels. For Washington, the risk is that policies aimed at containing China end up isolating the US — and hurting its businesses and consumers.

“China’s technological rise will not be stymied, and might not even be slowed, by US restrictions,” said Adam Posen, president of the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics, who has conducted research for governments and central banks around the world. “Except those draconian ones that simultaneously slow the pace of innovation in the US and globally.”

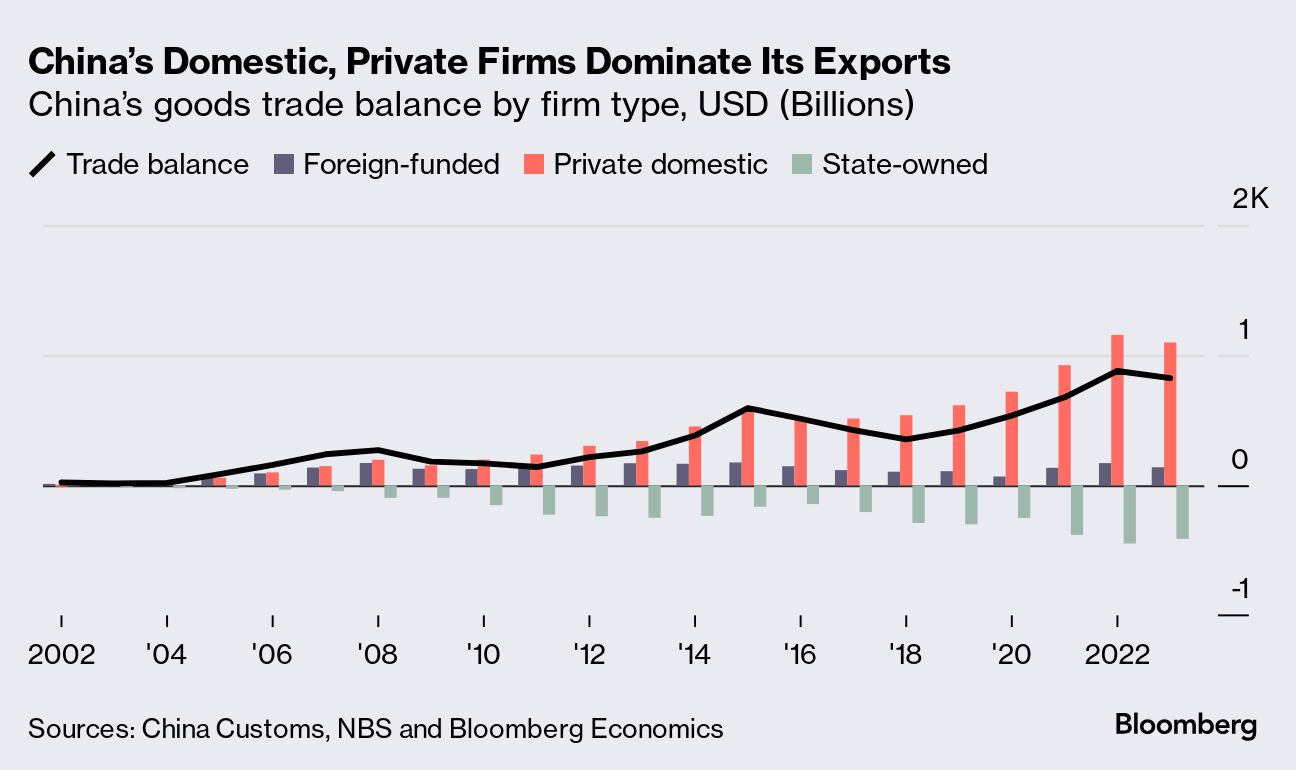

China’s production prowess is at historic heights: Its manufactured goods trade surplus is the largest relative to global GDP of any country since the US right after World War II. Chinese companies like BYD Co. and Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd., known as CATL, are world leaders in making goods such as EVs, batteries and solar panels — the pillars of Xi’s “new productive forces” to drive growth as authorities seek to deflate a property bubble.

China’s Goods Surplus Expands Despite US Barriers

Net exports of manufactured goods, percentage of global GDP

Sources: World Bank and Bloomberg Economics

While the Biden administration has stabilized US-China ties, the world’s biggest economies are set to remain locked in intense competition no matter whether Trump or Kamala Harris wins the White House on Nov. 5. The struggle now is focused on whether the US can prevent China from catching up in advanced technology like manufacturing the most cutting-edge chips used for AI, which are currently only made with equipment from ASML.

For policymakers in Washington and Beijing, the push to win the technology race is being driven by a number of considerations, including a desire to drive development, create jobs and secure supply chains. But officials in both capitals say another factor is playing a bigger role in economic policy these days: Preparation for a potential war, even if one isn’t imminent or planned.

US Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris. Photographer: Brandon Bell

The US has been explicit about this. In a landmark 2022 speech, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan outlined a series of technologies — including semiconductors, clean energy and biotech — in which the US would seek to “maintain as large of a lead as possible.” He called export controls “a new strategic asset” that could be used to impose costs on adversaries and “degrade their battlefield capabilities.”

The Communist Party also increasingly views a strong manufacturing sector as essential for national security in an extreme scenario like a war. Officials in Beijing see the capacity to produce energy from sources like wind and solar power as necessary to keep the economy moving if the US and its allies were to ever block off oil and gas supplies in a conflict over Taiwan or competing territorial claims with nations such as Japan, India or the Philippines.

China’s Domestic, Private Firms Dominate Its Exports

China’s goods trade balance by firm type, USD (Billions)

Sources: China Customs, NBS and Bloomberg Economics

The possibility of an all-out conflict means China has no intention of degrading its manufacturing power, despite US demands that Xi’s government reduce overcapacity and rebalance its economy more toward consumption. The Communist Party has resisted cash handouts to bolster growth even as it unveils a range of stimulus measures that have helped underpin a recent surge in Chinese shares.

There’s also a domestic political imperative: Officials in Beijing assess that factory closures fomented social instability in the US and led to the rise of Trump. They point out that American policy makers are now racing to rebuild manufacturing strength with subsidies to lure domestic production from chipmakers like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., known as TSMC, and South Korea-based Samsung Electronics Co.

Attendees ahead of a “First Tool-In” ceremony at the TSMC facility under construction in Phoenix in December 2022. Photographer: Bloomberg

“The CPC and the Chinese government view tech innovation as the core of national development,” Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian said at a briefing last month, referring to the Communist Party of China.

China Is Investing in High-Tech Sectors

Fixed asset investment, compound annual growth rate, 2015-23

Sources: NBS and Bloomberg Economics

Made in China 2025 shows how far Xi’s efforts have come. Although China is still struggling to develop manufacturing processes for advanced semiconductors — the main focus of US export controls — it now has a clear lead in EVs, automotive software and lithium battery technology, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. China’s LNG shipbuilding and high-speed rail industries are on track to hit targets. It also produces the world’s most efficient and lowest-cost solar panels, and is developing innovative drugs.

China’s Export Market Share in High-Tech Goods Is Growing

Sources: International Trade Centre, China Customs and Bloomberg Economics

“China continues to climb the ladder of manufacturing dominance and technological advance,” Bloomberg Economics and Bloomberg Intelligence said. “If the US wants to win the competition, Washington will need to run faster or try harder to trip China.”

On the campaign trail, Trump and Harris have advocated different approaches toward China, even as both agree on the need to thwart its rise.

US Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump. Photographer: Brandon Bell

Trump has vowed to renew the trade war on China that dominated his first term, threatening tariffs of as high as 60% — a level that would effectively end trade between the two nations, according to Bloomberg Economics.

Tariffs — long decried by economists as market-skewing impediments to productivity — have helped shrink America’s trade deficit with China on paper. But much of that commerce was rerouted through Southeast Asia and other places, and the urgency to find new markets has only bolstered Chinese manufacturing dominance in EVs and other areas.

BYD is a case in point. China’s top-selling automaker expects overseas deliveries to account for almost half of total sales in the future, suggesting it doesn’t see US tariffs — now at 102.5% — as a big impediment. The automaker already has a factory in Thailand and is building similar ones in Hungary, Brazil and Turkey.

BYD’s Yuan Pro EV during a launch event in Sao Paulo, Brazil in September. Photographer: Maira Erlich/Bloomberg

“We don’t need to enter the US market,” Stella Li, a BYD executive vice president, told Bloomberg in August from the company’s headquarters in Shenzhen, China’s main tech hub. “We’ve got a lot of opportunities to become a great company with the many markets outside of the US.”

Harris has criticized Trump’s plan for higher tariffs, saying they equate to a tax on the American middle class. On the campaign trail, she’s spoken of the need to prevent China from obtaining advanced chips, indicating she would continue President Joe Biden’s use of export controls. She’s also emphasized the need for investments “to ensure America remains a leader in the industries of the future.”

A senior White House official, who asked not to be identified, said the Biden administration’s tech curbs have succeeded in putting a ceiling on China’s development of high-quality semiconductors, allowing the US and its allies to retain significant advantages.

While Chinese companies have flooded the world with EVs and solar panels, their progress looks more uneven further up the technological value chain. In areas such as advanced semiconductors and chipmaking gear — the base layer for all future technologies — the country as a whole looks set to remain behind the US for years to come.

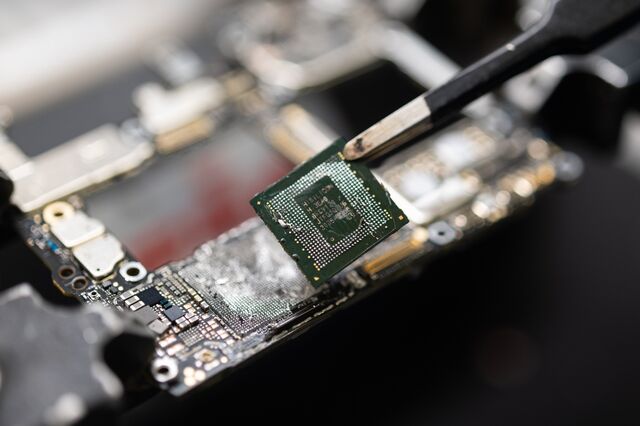

The US has banned China from buying the most advanced AI chips from Nvidia Corp. and Advanced Micro Devices Inc. It has also blocked Xi’s government from obtaining ASML’s extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) machines, which are essential to producing high-end chips, and is now seeking to hinder China’s ability to use deep ultraviolet lithography (DUV), an older technology that is underpinning the nation’s current production.

A visitor takes photos of an ASML mask aligner during the third China International Import Expo in November 2020 in Shanghai. Photographer: Zhang Hengwei/China News Service/Getty Images

Without even ASML’s DUV gear, it will be much harder for Chinese technology champion Huawei Technologies Co. and its partner Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. to make breakthroughs in their current capability, which lags several generations — roughly half a decade — behind industry leader TSMC.

Even less clear is Chinese advancements in AI — regarded as one of the key determinants of future economic and geopolitical power. While OpenAI, Microsoft Corp. and Google continue to publicize new AI developments and support a thriving startup ecosystem, Chinese companies like Baidu Inc. labor under chip and data-content restrictions, and have yet to show evidence of significant breakthroughs.

The US export controls announced on Oct. 7, 2022 “made it much more difficult for scaled domestic Chinese production of strategically important chips like the most advanced AI accelerators,” said Jordan Schneider, founder of the ChinaTalk newsletter and adjunct fellow at the Center for a New American Security. Even so, he added, “uneven execution on the stated intentions of the export controls, particularly on the semiconductor equipment manufacturing side, have made the past two years post Oct 7th far easier for Chinese semiconductor firms than they could have been.”

Chinese firms have stockpiled a record amount of semiconductor equipment this year, including high-end Nvidia chips, in anticipation of further restrictions. Bloomberg Intelligence says those stores, along with more efficient computing processes, “should ensure China’s AI development remains on track through 2025 and beyond.”

China Is Stockpiling ASML Lithography Machines

Sources: China Customs, National Bureau of Statistics and Bloomberg Economics

Huawei, the company at the heart of Beijing’s global tech and semiconductor ambitions, shows China’s resilience. When the company saw its sales plummet after the US first placed it on a trade blacklist in 2019, it poured money into research and development and began working with domestic suppliers. Huawei’s smartphone business has since recovered and is now challenging Apple Inc.

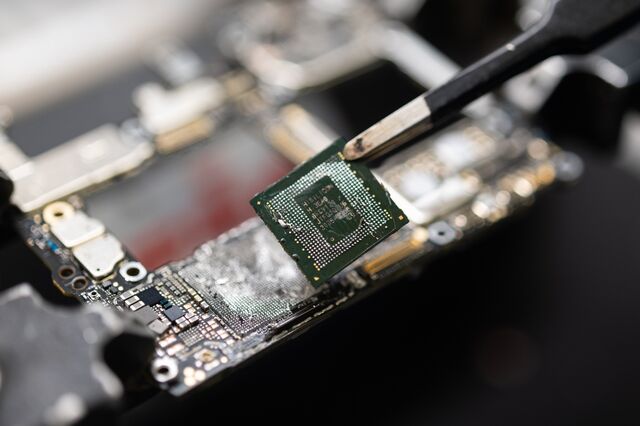

Last year, Huawei introduced a smartphone with a 7-nanometer chip — something the US thought was unrealistic for Chinese firms to manufacture with DUV technology. In a show of bravado that spurred patriotic memes on Chinese social media, Huawei unveiled the breakthrough with great fanfare just as Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, the top US sanctions enforcer, was touring China.

A Kirin 9000s chip fabricated in China by SMIC taken from a Huawei Mate 60 Pro smartphone. Photographer: James Park/Bloomberg

Bloomberg Intelligence says Huawei’s latest semiconductors could outperform Nvidia’s H20 AI chip, a less powerful product that the California-based company developed for the Chinese market to comply with US restrictions. Bloomberg reported that Chinese regulators have discouraged local companies from purchasing Nvidia’s H20 chips, a move aimed at bolstering the market share of Huawei and Beijing-based AI chipmaker Cambricon Technologies Corp., which saw its shares surge on the news.

China could lift general chip self-sufficiency to 40% by 2030, nearly double from 2025, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. projected in a recent report, although most of that capacity expansion would be limited to older-generation semiconductors.

Huawei’s production campus in Dongguan, China. Photographer: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images AsiaPac

US officials have downplayed China’s tech advances, saying the process it’s using to develop chips like the one used in the Huawei phone is inefficient and commercially unviable without ASML’s EUV lithography machines. In an interview during an August trip to Beijing, Sullivan — Biden’s national security advisor — said that China’s efforts to stockpile Nvidia chips has “a clock on it” and the US was striving to “up our game” to stop Xi’s government from obtaining semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

But China also appears to be making notable advancements in that area. Beijing recently advised state-linked organizations to use a new homemade lithography machine with a resolution of 65 nanometers or better. While that’s far from the 8-nanometer resolution of ASML’s best machines, China’s most advanced indigenous equipment previously was only capable of about 90 nanometers.

Bloomberg Economics research shows that China has overtaken the US in international patent applications, which are stretching across a broader range of areas. That’s a positive signal for China’s efforts to commercialize new technologies — even as questions remain over whether its patents are more incremental than innovative.

China’s Patents Are Increasing Across Technologies

Percentage of world’s PCT patent publications by sector

Sources: World Intellectual Property Organization and Bloomberg Economics

China recently publicized a patent application from Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment Group Co., known as SMEE, for an EUV lithography machine. If it gets to market — a big “if” given how complicated they are to make — the Chinese company would be the only one in the world apart from ASML capable of manufacturing such equipment.

The US export controls generated “massive incentives” for Chinese firms to collaborate more among themselves, according to Paul Triolo, partner for China and Technology Policy Lead at Washington-based advisory firm Albright Stonebridge Group. While Huawei’s AI chips aren’t comparable to those from Nvidia and Apple, he said, “they are capable enough for many applications.”

“Major progress has been made in moving towards manufacturing processes that minimize the use of particularly US tools,” Triolo said. “This process will be slow and challenging, particularly as the US continues to ratchet up controls targeting both tool makers and front-end manufacturing facilities.”

At the moment, US lawmakers are pushing ahead with more measures to wall off Chinese technology. An expanding list of products and services that transmit data — as most things now do in the modern world — are now seen as threats to national security.

Earlier this year, Biden signed a law requiring Chinese-based parent company Bytedance Ltd. to divest from TikTok or face a US ban of the popular social media site. And last month, the US House passed what’s known as the Biosecure Act, a bill that would blacklist Chinese biotech companies from lucrative US-funded research if it becomes law.

TikTok’s offices in Culver City, California. Photographer: Bing Guan/Bloomberg

The US’s focus on national security is making it a global outlier, particularly when it comes to EVs. While the European Union, Brazil and Turkey have raised tariffs on Chinese EVs, they have also welcomed companies such as BYD — which now sells more electric cars than Elon Musk’s Tesla Inc. — to set up factories and build locally.

“The efforts to contain China worked in the short term,” said Shen Meng, a director at Beijing-based investment bank Chanson & Co. “But in the long run China will find ways to circumvent this containment.”

Trump has indicated an openness for Chinese automakers to build cars in the US as a way to create jobs, but it’s unclear what he’ll do should he win the election. While he was president, his administration at one point advocated for a “Clean Network” in which no data from American citizens would be accessible to China — an idea that ended up going nowhere.

Harris would be likely to follow the current White House, which is now seeking to ban Chinese-made hardware and software for automobiles due to national security concerns, effectively blocking all Chinese EVs from operating in the US. Such a restriction also risks spreading to any Chinese-made product that transmits data, from televisions to washing machines.

An assembly line at BYD’s plant in Nikhom Phatthana, Thailand, in July. Photographer: Valeria Mongelli/Bloomberg

China, for its part, is doing more to protect its own tech. Beijing has strongly advised its carmakers to make sure advanced electric vehicle technology stays in the country, with key components produced domestically and then sent for final assembly in other factories around the world.

All of this means it’s becoming harder for global companies to operate in both the US and China, Peter Mandelson, a former European trade commissioner who co-founded the consulting firm Global Counsel, said during an interview in Hong Kong.

“A rupture has emerged,” said Mandelson, now a close adviser to UK leader Keir Starmer. “This is a very strong headwind blowing across the global economy, and international companies need to navigate that.”