Archaeologists in Turkey have discovered and deciphered a 3,500-year-old clay tablet, finding that it details a shopping list for a “large amount” of furniture that’s not so different from today’s inventory.

The first lines of the newfound tablet, which dates to the 15th century B.C., detail a large purchase of wooden tables, chairs and stools. While it’s unclear who wrote the tablet and who made the transaction, “this tablet is useful for understanding the economic structure and state system of the Late Bronze Age,” Mehmet Ersoy, Turkey’s minister of culture and tourism, said in a translated statement.

The furniture list contains Akkadian cuneiform, a logo-syllabic writing form common in the ancient Middle East. Now considered extinct, Akkadian is one of the earliest known Semitic languages spoken and written from the third millennium B.C. until the first century A.D. The language is related to Arabic and Hebrew and was used across a vast geographical area spanning Iran to Egypt and southern Iraq to central Turkey.

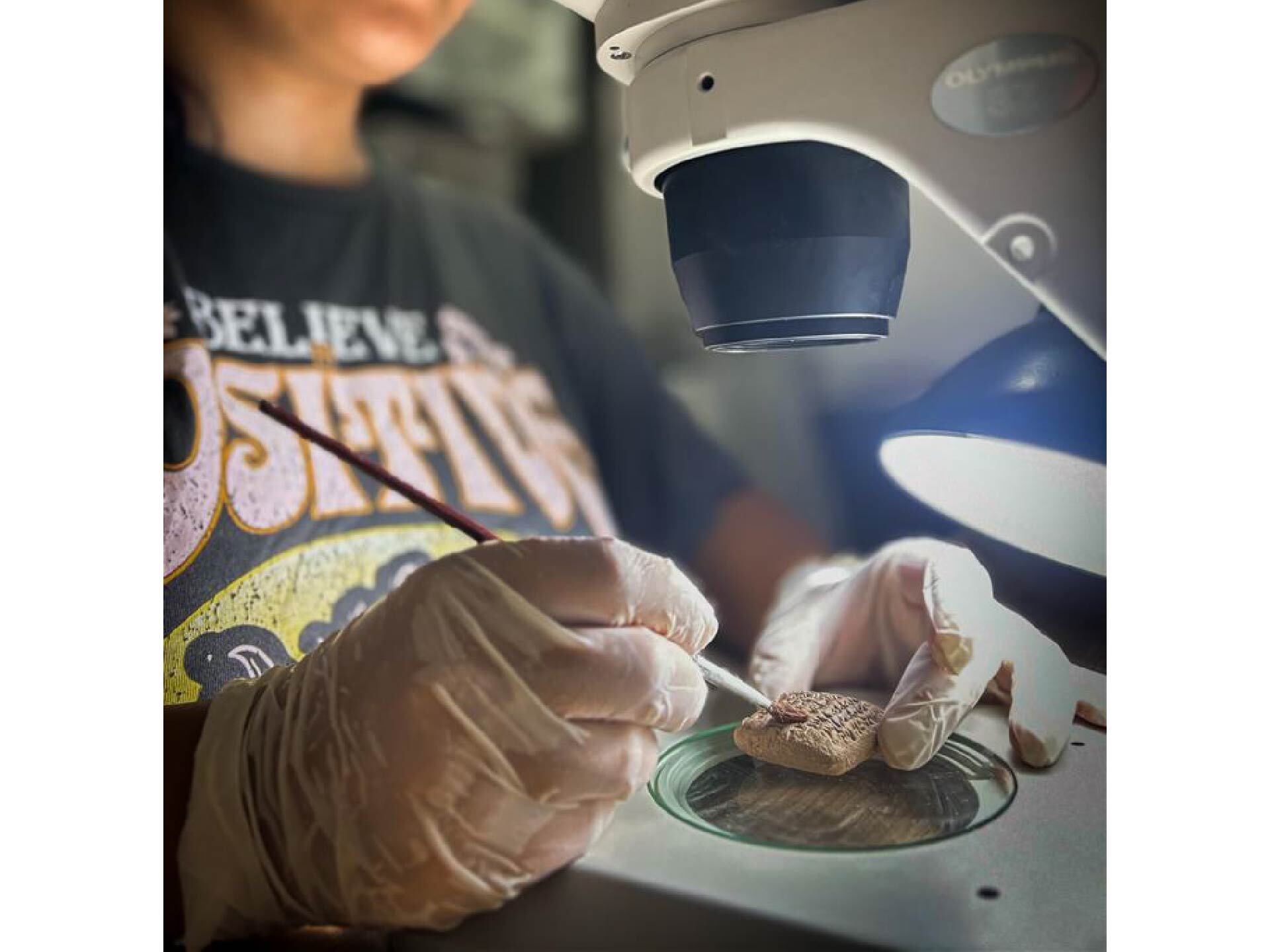

An excavation team found the tablet, which measures 1.6 by 0.6 inches (4 by 1.6 centimeters) and weighs 0.06 pound (28 grams), during restoration work after an earthquake shook the Old City of Alalakh in Hatay’s Reyhanlı district.

Alalakh, now an archaeological site known as Tell Atchana, sits near present-day Antakya in southern Turkey. In the second millennium B.C., Alalakh was the capital city of the Kingdom of Mukish and the largest settlement in the region. The Amorites, a Semitic-speaking people from western Mesopotamia (modern-day Syria), occupied the area, which is now covered with large mounds, or “tell.”

Related: What’s the world’s oldest civilization?

In the 15th century B.C., the city of Alalakh belonged to the Mittani Empire. The region was known for its local production of pottery, metal and glass. By 1350 B.C., King Shattiwaza of the Mittani Kingdom ceded Alalakh and the area west of the Euphrates River to the Hittite king Suppiluliuma. Archaeologists are now studying tablets found in ancient castles and palaces to understand the social dynamics of the region.

The excavation team in Turkey is working with Johns Hopkins University Assyriologist Jacob Lauinger and his doctoral student Zeynep Türker to learn more about the tablet.

“We believe it will offer a new perspective,” Ersoy said.